Khalid Mustafa Medani, Black Markets and Militants: Informal Networks in the Middle East and Africa. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2021)

There’s been a lot of great academic research on the resurgence of Islamist political activism in the 1970s in recent years, including Carry Rosefksy Wickham’s The Muslim Brotherhood, Khalil al-Anani’s Inside the Muslim Brotherhood, Victor Willi’s The Fourth Ordeal, Stephane Lacroix’s Awakening Islam and recent work on Egypt, Courtney Freer’s Rentier Islamism, Marie Vannetzel’s The Muslim Brothers in Society, Tarek Masoud’s Counting Islam, Steven Brooke’s Winning Hearts and Votes, Hisham Sallem’s forthcoming Classless Politics, and so many more. What, one might wonder, could be left to say?

In Black Markets and Militants, Khalid Mustafa Medani presents a genuinely fresh look at the rise of Islamist politics in the 1970s. He does this by shifting the theoretical lens from religious, organizational and political factors explored in much of the literature to political economy and variations in state capacity. And he does it through his choice of case studies, comparing Egypt not to Tunisia or Jordan but to Sudan and Somalia. The result is one of the freshest and most challenging books on political Islam that I’ve read in quite a while, with a wealth of new empirical detail and a bold reframing of the theoretical lens through which we view Islamist politics. I talked with Medani about the book in the fall on my podcast, and have been reflecting on it ever since.

Let me start with the comparative strategy. The vast majority of research on Islamist politics in the Middle East has confined itself to the countries of the Arab world. There are good reasons for that: most of those academic researchers speak Arabic and are trained primarily on Arab or “Middle East” politics, and there are dense networks connecting Muslim Brotherhood-style organizations across the region. There’s a lot of value in comparing Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood to Tunisia’s Ennahda, Morocco’s PKD, or Jordan’s Muslim Brotherhood. The different evolution of Islamism in the Gulf, as Lacroix and Freer show brilliantly, makes stark the importance of local context and specific religious networks.

But there are real costs to limiting the comparative universe to “the Middle East,” as I argued recently in Foreign Affairs. Medani’s book is an exemplar of the kind of cross-regional and transregional comparison which can invigorate scholarship: cross-regional by comparing Egypt with Sudan and Somalia; transregional by showing how those cases are differently impacted by similar global processes such as oil booms and busts, labor remittances, and marketization.

The inclusion of Sudan is particularly important and welcome. Sudan has long occupied a strange liminal status: too African for Middle East Studies, too Middle Eastern for African Studies. The 2019 revolution has changed that, to some extent, but not nearly enough. For those interested in Islamism, it’s hard to explain ignoring one of the only states actually ruled by Muslim Brotherhood-style Islamism (Noah Salomon’s For the Love of the Prophet is one of my favorites on this). Sudan’s Islamist thinkers like Hassan Turabi and its governance efforts were quite familiar to the Islamists of the Arab world. Osama bin Laden, too, spent a few years in Sudan. Medani makes the most of this comparative lens, in ways which allow us to see much more clearly certain developments in both Egypt and Sudan.

So what’s the argument? Medani focuses our attention on the impact of several related but distinct global economic developments: the oil boom and bust cycles of the 1970s and 1980s, patterns of labor migration and remittances, the rise of Islamic banking, and the retreat of the state under the pressures of neoliberal reforms. The oil boom of the 1970s attracted millions of migrant workers who often sent their remittances back home through informal, unregulated banking systems. As Medani puts it, “these capital inflows resulted in the rise of strong autonomous informal economic sectors and altered the socioeconomic landscape of all three countries in profound, but divergent, ways.” He argues that social ties and trust became the key to the functioning of these informal financial flows — and Islamists proved particularly good at filling that role. For Medani, it isn’t so much the Wahhabi ideas that are migrating from the Gulf, it’s the money - as mediated through informal financial institutions where Islam could stand in for the state as a reason to trust.

It’s not new to link the rise of Islamism to the flow of remittances from the Gulf, but Medani goes beyond that simple connection with a highly detailed, empirically rich exploration of the mechanisms and institutions of the emergent informal Islamic banking sectors in each country. Here he points to variation in state capacity, the reach and effectiveness of state institutions, to explain some of the divergent outcomes. In Egypt, neoliberal reforms led the state to not only tolerate but to empower the Islamic banking sector, while at the same time to withdraw from social services and other sectors once under the purview of the state, creating demands which increasingly well funded Islamists could fill.

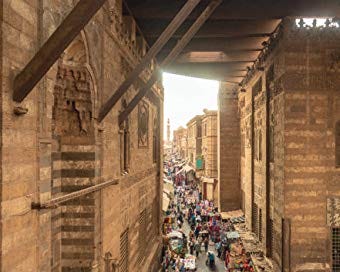

Where other excellent recent scholarship focuses its gaze on university student politics, Medani pays more attention to Cairo’s informal housing projects and to its booming Islamic financial sector as the incubators of Islamist politics. In a sense, he brings poor and nouveau riche Egyptians back in to the story. He tells a familiar story of the Egyptian regime’s economic liberalization under Sadat and Mubarak, but with a twist: the Islamic banks and economic enterprises of the Muslim Brotherhood, he shows, benefited greatly from those reforms and the state benefited from their brokerage role. He details the rise of an “Islamist bourgeoisie” with a dense network of Islamic financial institutions handling vast flows of remittances, creating an informal economy closely tied to the Gulf and the broader regional economy and operating in parallel to the formal economy.

In Sudan under Omar Bashir, by contrast, the state sought to monopolize those “Islamic” financial flows and fought hard against any other actors seeking to cut into those black markets and generate the financial capabilities to mount a challenge to the regime. Medani locates the success of the Muslim Brotherhood in Sudan in the “monopolization of informal financial markest and Islamic banks by a coalition of a newly emergent Islamist commercial class and mid-ranking military officers.” He argues that was the relative weakness of Sudan’s state that allowed Turabi to push sharia so effectively: the Brotherhood’s control over these Islamic financial institutions and ability to profit from remittance flows made it more powerful in many ways than a bankrupt and incompetent state. As Bashir’s regime aged, however, the challenges of an informal financial sector changed, as did the demands of coercive power as remittances dwindled.

There’s a lot more than that to this fascinating, rich book. Medani traces the effects of the oil bust as well as the booms, the ownership of Islamic financial institutions, the politics of informal housing neighborhoods like Imbaba the battles between Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood and the state, and more at granular level of detail. He makes clear the economic and institutional stakes of Egypt’s brutal crackdown post-2013 on the financial foundations of the Brotherhood’s power, as well as the stakes for the military of the 2019 Sudanese revolution toppling the Bashir regime. He also explores how this all plays out in the failed state of Somalia, which raises a whole other set of issues. This is a book well worth reading for anyone interested in political Islam in the Arab world, the economic foundations of the Islamist resurgence, the political effects of globalization and neoliberal reforms, and the microfoundations of labor remittances from the Gulf.