Does Lebanon's election change anything?

There were some interesting results. But its political problems run deep.

I must confess that it was hard to get too excited about Lebanon’s Parliamentary elections. The prospects for any meaningful change via electoral politics just seemed too remote given the long-standing dominance of an entrenched sectarian party cartel and the country’s massive economic, social and governance crisis. They still do. But at the same time, the victory of thirteen independent oppositional candidates in a system designed to prevent such victories does represent something new. Even if they will likely struggle to make much impact on the country’s massive governance failures, economic crisis, and political stalemate, these victories represent a tangible political result of years of popular mobilization.

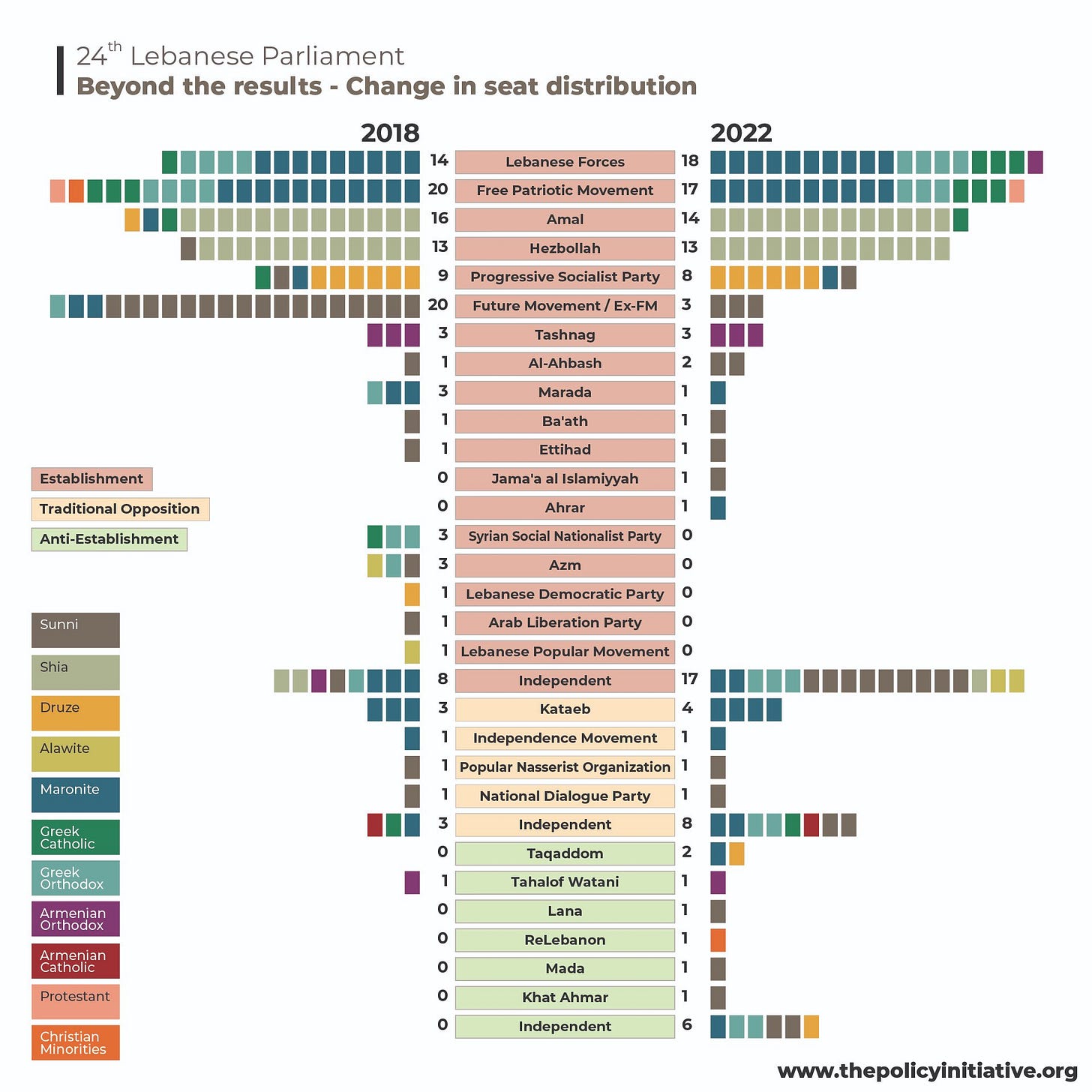

The immediate readout, at least in Washington policy circles, was that the election represented a defeat for Hezbollah - a “major defeat,” even. It’s hard to really sustain that reading, though. Hezbollah didn’t lose any seats, and more importantly Parliament isn’t really the key institutional locus for its power. In my Middle East Political Science Podcast this morning, Sami Atallah of The Policy Initiative pointed out that Hezbollah declined to distribute extra votes to certain Shia partners which could have allowed them to hold their seats. He suggests that this could have been a signal of Hezbollah’s displeasure with its allies aligned with the Syrian regime - perhaps because of Bashar al-Asad’s recent visit to Abu Dhabi, perhaps for more local reasons. Maybe Hezbollah didn’t want the burden of a Parliamentary majority given the staggering challenges which the next government will have to try and face. Either way, Hezbollah’s power continues to lie more in its weapons, control, ideology and mobilizational ability than in the number of MPs it controls.

The shift within the Christian vote from a slight FPM majority to a slight Lebanese Forces majority does tilt that balance of power a bit, presumably with policy implications in line with the anti-Hezbollah stance of the LF’s Saudi backers. But there isn’t enough of a majority to give anti-Hezbollah forces any kind of governing majority. I agree with Thanassis Cambanis that the new Parliament will likely be just as deadlocked as the old one. Government formation will likely be contentious, some new faces may take positions, but ultimately all within the same cross-sectarian party cartel unified by elite corruption and impunity. Hezbollah is very much a part of that party cartel — as the 2019 protest movement made clear with its slogan “all of you mean all of you” — and that won’t likely change. For essential theoretical and empirical background on the political economy of this elite sectarian party cartel, I highly recommend the work of Bassel Salloukh, Hannes Baumann, Tamirace Fakhoury, and others.

Source: The Policy Initiative

The more interesting result of the election was the remarkable victory of thirteen independent opposition candidates, who for the first time managed to break through the electoral domination of the sectarian party cartel. These opposition winners came from diverse backgrounds, as Sami Atallah and Christiana Parreira previewed just before the election. Some are old elites rebranded. But many are genuinely associated with the 2019 protest movement and ran as a direct repudiation of “the regime” - the entire sectarian party cartel, not of any one political party. They managed to unseat some of the most unsavory Parliamentary figures associated with elite corruption and the banking crisis. They could use their Parliamentary posts to demand oversight, spotlight the urgent issues facing a desperate population, and perhaps push for the removal of particularly odious entrenched officials. And, as Tamirace Fakhoury and John Nagle point out, “the success of these independent candidates demonstrates that anti-sectarian politics can succeed in an environment designed to prohibit it flourishing.”

As galvanizing as these individual victories were, as Halim Shebaya points out, the independent Change candidates didn’t win enough seats to hold the balance of power in Parliament, and most of the incumbent politicians they opposed still held their seats. The party cartel system is designed to prevent any meaningful challengers from outside the sectarian system, and those elites will more likely circle the wagons rather than embrace the lesson of popular demands for change. We shouldn’t exaggerate what these independent MPs will be able to accomplish - but we can still revel in their ability to win against great odds, and hope that this will have positive interaction effects with popular mobilization to keep the spirit of the 2019 protest movement alive.