How Egyptians Became Colored

A new book shines light on the wartime racialization of Egypt in the British Empire

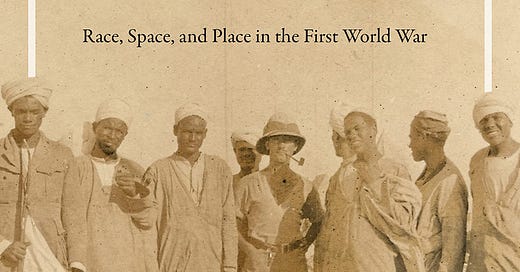

Kyle J. Anderson, The Egyptian Labor Corps: Race, Space, and Place in the First World War (University of Texas Press, 2022)

Sometimes, a book you pick up at random based on a promotional tweet turns out to be a real gem. The Egyptian Labor Corps: Race, Space, and Place in the First World War by Kyle Anderson is one of those. I decided to check it out because it hit right at the convergence of several themes I’ve been spending a lot of time with lately: the late/post-Ottoman period in the Middle East, and racial formations and racialization across the Middle East and Africa. Even though I wasn’t familiar with the author, how could I resist a book which promised to look at racialization in Egypt in the First World War?

I’ve been fascinated by the racial complexities of Egypt ever since I first read Eve Troutt Powell’s A Different Shade of Colonialism. During my times living in Cairo, I was frequently horrified by the treatment of Sudanese and other African migrants, and I was shall we say unpersuaded by the recent Arab Barometer finding that only 6% of Egyptians - the lowest percentage of any country surveyed - thought that discrimination against Black individuals was a problem in their country. I have become even more interested in the complex historical evolution of Egyptian attitudes towards Africa, Africans and race (as well as the complex local and transregional interactions between pan-Arabism and pan-Africanism) since launching the ongoing POMEPS-PASR Racial Formations in Africa and the Middle East project with Hisham Aidi and Zachariah Mampilly (stay tuned for the next iteration of that project). Those publications included essays on themes such as Egyptian African Studies (Zeyad el-Nabolsi), the Aswan Dam and Afro-Arab Solidarities (Bayan Abu Bakr), and the legacies of Nubia in Egyptian identity (Yasmine Moll).

Kyle Anderson’s fascinating new book convincingly presents the Egyptian Labor Corps, created by the British to support its efforts in World War I, as a pivotal moment in the articulation of racialized understandings of Egyptian identity. He draws on a wide range of sources, from British archives to Egyptian newspapers to contemporary music recordings, to explore the ELC from multiple perspectives. He shows compellingly how central that experience was at a pivotal moment in Egyptian history, and how it’s been largely forgotten - or, in the classic tradition of nationalist histories, misremembered.

The Egyptian Labor Corps brought nearly half a million young Egyptian men, most of them forcibly conscripted from the countryside, to serve as military laborers. It was never directly involved in combat, but played a pivotal role in building critical logistical infrastructure in support of the British war effort across the many theaters of the war but especially in the Sinai, Gaza and the rest of Palestine. Laborers were technically recruited, with vague contracts which often went unhonored, but in practice this often translated into young rural men rounded up and chain-ganged into service, “tied by ropes and driven away like cattle.”

Anderson recounts the horror these scenes engendered among Egyptians, in part because they associated such images with Black African slavery; their shock was not so much with the slavery as with it being applied to Egyptians: “the men of the Wafd lambasted the hypocrisy of what the British called ‘voluntary’ recruitment, insisting that what was happening with the ELC was closer to slavery (‘ibudiyya). Representations comparing ELC workers to “Black slaves” (zunuj), “men of color” (hommes de couleur), and “African savages” (washush ifriqiyya) drew their mobilizing force from popular conceptions of national identity that posited Egyptian racial difference from, and superiority to, Black Africans.” Towards the end of the book, he traces how Egyptian nationalists reacted to images of the forced conscription of Egyptians reminiscent of images from African slavery. He ties this horror to the move towards promoting distinctive new forms of Egyptian nationalism to challenge their equation with Black Africans and assert Egyptian racial superiority. The ELC, he argues, played an important symbolic role in the 1919 revolution, profoundly shaped the emergence of neo-Pharaonic identity claims, and shaped the later emergence of Egypt’s distinctive encounter with pan-Arabism and pan-Africanism.

Anderson identifies several critical moments of racialization in the construction and service of the ELC. Early in the book, he shows how the creation of the ELC moved Egyptians across the global “color line.” The key moment, he suggests, came when the British shifted from viewing Egyptians primarily as Muslims who might be radicalized by a call for jihad by the Ottoman Caliph to viewing them primarily as colored colonial subjects. He quotes Lord Kitchener just prior to the war describing Egyptians as “Mahommedan”, and uses British archives to detail imperial concerns over their potential loyalties to a Ottoman caliphate. But when that didn’t manifest, the British rapidly turned to the Egyptians as they did to so many of their colonial subjects as a source of manpower for the global war. “Over the course of the war,” he writes, “British authorities increasingly racialized Egyptians as a source of manpower alongside Black, Brown, East Asian, and Indigenous people across the globe.” The British, like the French and other colonial powers, had developed quite detailed beliefs about the hierarchies among colonized peoples and their suitability for different forms of service. The Egyptians fell into the category of colonized coloured who would be put to hard labor, but not sent into battle. The ELC thus became “part of the ‘Coloured Labor Corps,’ classifed as ‘negroid',’ and called derogatory racial epithets.”

In several chapters, Anderson closely observes the organization and practices of the labor camps themselves, showing both the racist behavior of British officers and the forms of solidarity among Egyptians which emerged under the harsh conditions. It’s hard to not be shocked by the casual racism in ELC officer Earnest Venable’s letters and documents (Anderson has to black out many racial epithets as he quotes from them), as well as Venable’s distinctive racial hierarchies (he prefers Sudanese and Nubians - “the blacker the better” - to the Egyptians who he places lower on “the scale of civilization”).

Their labor conditions were brutal. Egyptians from hot climates struggled with the intense cold and rough weather in the northern Sinai deserts and Palestine, with thousands dying from the conditions. He pays careful attention to the spatial organization of the camps, which made “race viscerally real” for the Egyptians. There, the Egyptians and other “coloured” laborers were segregated from their white officers, confined to camp when not working, and subject to what Anderson calls a caste system “with seperate hospitals and prisons for Egyptians, Indians, and white troops.” On the flip side, Anderson offers detailed and fascinating accounts of the solidarities formed among Egyptians, their athletic competitions and popular work songs and subversive commentaries on their British officers.

The Egyptian Labor Corps is a good read which makes creative and thorough use of a wide range of available source materials to produce a compelling vignette of a critical and largely forgotten moment in Egyptian and colonial history. It makes a solid contribution to the literature on race and racialization in Egypt, with much more wide ranging implications for British imperial history. It also offers intriguing depth to the later complexities of Egyptian nationalism’s place within pan-Arabism and pan-Africanism — topics I’m now even more keen to learn more about.