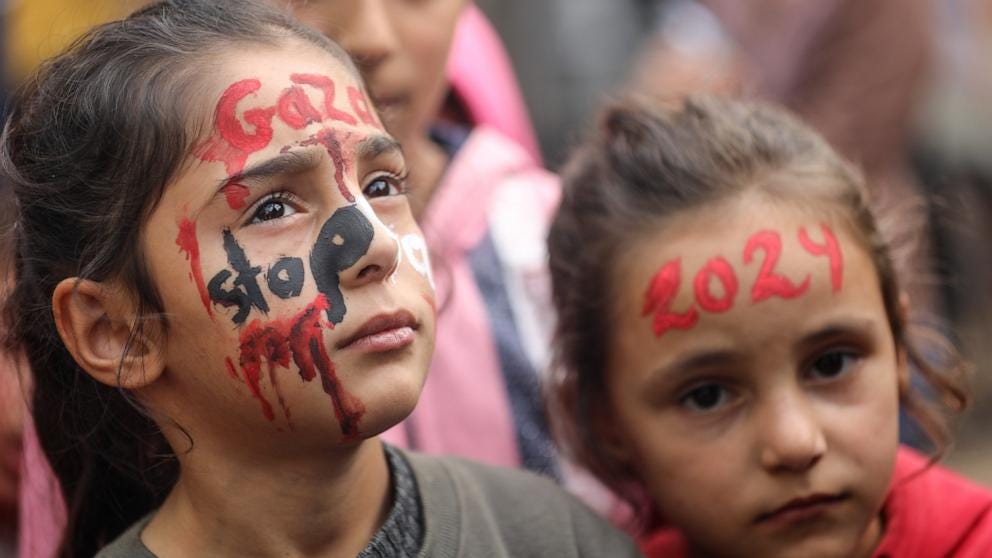

What can I say about 2023? It was a year, both for me personally and for the Middle East. 2024 shouldn’t try to top it, that’s all I’m going to say. I’ll have a lot more to say about the year that was, and the year to come, very soon. Let us all hope for an end to Israel’s war in Gaza and a massive effort to help the devastated people there very early in this new year, and do everything in our power to make it happen. But for now, let’s stick to the basics: welcome to the 16th edition of Abu Aardvark’s MENA Academy Weekly Roundup, and the first of 2024!

Before I get into all the great research which crossed my desk the last two weeks, I wanted to point out two great opportunities. First, MERIP — one of the absolute treasures of cross-disciplinary research and writing on the Middle East — is looking to hire a new executive director. Check out the details here to see if you might be a good fit.

Second, the APSA MENA Politics Section has extended its deadline for their dissertation award. This is an outstanding opportunity to have original, well-conceived and well-executed research recognized. Please note that the Section isn’t accepting self-nominations, so advisers — this is on you. Do right by your students. Here’s the details:

Awarded for the best doctoral thesis defended in the previous academic year. (August-July). To be considered, the dissertation must be nominated by the dissertation adviser or another faculty member familiar with the work; self-nominations are not permitted and dissertations may only be nominated once. The nominator should submit a short letter explaining why the dissertation makes an exceptional contribution to the study of the politics of the Middle East and the broader discipline of Political Science; this letter should also indicate if any portion of the dissertation has been published in article format and/or if it is being nominated for another section award. Work utilizing any methodological, theoretical, and empirical tools for the study of the politics of the Middle East and North Africa will be considered. Please submit nomination letters, with the dissertation as a PDF attachment, to the chair of the award committee with the subject heading “MENA Politics Best Dissertation Nomination” at apsamena@gmail.com by January 15.

And now, on with the roundup! This week, we first feature several special sections of journals along with some standout standalone articles. We begin with a roundtable orchestrated by Morten Valbjørn and Jan Busse on the perennial area studies controversy thematic, this time looking at how it plays out in different global and regional contexts; it resonates nicely with the Tom Pepinsky World Politics article I included in last week’s roundup. Next, there’s a truly rich special section in the journal Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East edited by Rosie Bsheer and Mohammed Alsudairi which explores transregional Cold War connections between the Middle East and Asia - not to be missed! Finally, from a fascinating roundtable discussion of Mahmoud Mamdani’s Neither Settler Nor Native I highlight the contribution about settler colonialism in Palestine by Nadia Abou el-Hajj, a truly timely topic given current political controversies.

In addition to those collections, we spotlight some great standalone articles: Hesham Sallam’s trenchant critique of the first decade of Sisi’s regime in Egypt; an agenda-setting study of official religious insitutions as instruments of autocratic control, by Ani Sarkissian and Ann Marie Wainscott (aka Umm Hazel!); Mashuq Kurt’s fascinating study of youth radicalization in Turkey; and Heba Alnajada’s deeply researched study of land claims in a Palestinian refugee camp in Jordan. Hope you find something in this rich set of research publications to get you inspired in the new year!

ROUNDTABLES

(A) THE AREA STUDIES CONTROVERSY

Jan Busse, Morten Valbjørn, and a cast of thousands, “Contextualizing the Contextualizers: How the Area Studies Controversy is Different in Different Places,” International Studies Review (December 2023). ABSTRACT: As part of recent years’ efforts at reaching a more context- and diversity-sensitive study of international relations, the nexus between fields of IR and Area Studies (AS) has received a renewed attention. While AS is usually presented as the “contextualizer” of the disciplines, this forum reverses the perspective by suggesting that an awareness of both diversity and context is also relevant when it comes to understanding the evolution of the field of AS and its relations to IR. In this forum, a selection of scholars with diverse backgrounds (US, Middle East, Europe, Latin America, Africa, and Central Asia), different (inter)disciplinary trainings and regional orientations examines how various fields of AS and its relations to the disciplines vary, and what follows from a stronger attention to such kind of diversity. By contextualizing the contextualizers, the forum brings attention to how a context-sensitive field can also suffer from its own provincialism. While the US-centric narrative about AS might have been almost “hegemonic,” at closer inspection, it turns out that AS in different (sub)disciplinary and geographical settings have evolved differently, and in some places the so-called Area Studies controversy (ASC) has been almost absent. A broadening of the perspective also reveals how the challenges to a successful cross-fertilization are not limited to those outlined in the “classic” ASC, but the forum does simultaneously offer encouraging lessons on how dialogues between area specialists and discipline-oriented scholars can help to overcome epistemological, theoretical, or methodological blind spots. Rather than presenting the IR/AS nexus as a panacea per se, the aim of the forum is therefore to invite to a broader and more self-reflective discussion on some of the opportunities as well as challenges associated with this strategy for making the study of international relations more context-sensitive and attentive to different forms of diversity.

(B) INTER-ASIAN COLD WAR LINKAGES: THE MIDDLE EAST IN THE WORLD

Rosie Bsheer and Mohammed Alsudairi, “Introduction: Inter-Asian Cold War Linkages: The Middle East in the World,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East. ABSTRACT: This introduction to the special section “Inter-Asian Cold War Linkages” shows how an interdisciplinary group of ten scholars take up the understudied Cold War linkages between the Middle East, on the one hand, and East and South Asia on the other. They examine how the inter-Asian lens allows us to rethink the history of the twentieth-century Middle East. Central to such rethinking is the destabilization of some of the dichotomous categories that were normalized during the Cold War and that have greatly shaped how we view culture, economy, politics, and society. These include the categories of state/nonstate, national/transnational, revolution/counterrevolution, religion/secularism, and private/public. Instead of taking these dualities for granted, the scholars here foreground the blurred and dialectical relationship between them, utilizing the Middle East as a site of critical analysis, learning, and theorizing and putting its study in conversation with the more Asia-centric and transnationally attuned literatures of the global Cold War. In the process, alternative genealogies and relationalities of the Middle East emerge, ones that place the Middle East in the world rather than prioritize how “the world” has acted on the Middle East, usually as a periphery or site of intervention. Doing so brings into view new ways, periodizations, and scales of studying the global Middle East in general and the Cold War in particular. FEATURING: Marral Shamshiri, “Revolutionary Transnationalism in the Persian Gulf: Iranian-Arab Solidarity in Dhufar in the 1970s”; Jeremy Randall, “Global Revolution Starts with Palestine: The Japanese Red Army's Alliance with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine”; Sara Farhan, “Pox and Proximities: Iraq's Cold War Medical Diplomacy”; Esmat Elhalaby, “Nonalignment and Its Forms of Knowledge”; Mohamed Elsayed Bushra, “A Salafi Pioneer of Saudi Anti-Communism: Muhammad Sultan al-Ma‘sumi al-Khujandi (1880–1961)”; Mohammed Alsudairi, “Forging an Anti-Bandung: Saudi Arabia and East Asia's Cold War”; Siarhei Bohdan, “Another Third Worldism?: Iranian Islamists’ Partnership with North Korea during the Cold War”; Max Ajl, “Planning in the Shadow of China: Tunisia in the Age of Developmentalism”; and Janice Hyeju Jeong, “South Korean Labor and Infrastructure in Saudi Arabia during the Late Cold War.”

(C) MAHMOUD MAMDANI’S NEITHER SETTLER NOR NATIVE

Nadia Abu el-Hajj, “Surviving colonialism? A response to Neither Settler nor Native,” Anthropological Theory (December 2023). ABSTRACT: This article engages Mahmood Mamdani's arguments in Neither Settler nor Native from the perspective of the question of Palestine. Sympathetic with his call to “decolonize the political” by severing nation from state, I, nevertheless, query his proposal to abandon, a priori, binaries such as “settler/native” and “perpetrator/victim” in order to achieve a decolonized state and polity. The unifying concept of the “survivor” that he proposes—that we are all survivors of the ravages of political modernity, I argue, has its own history and grammar of injury, victimhood, and identity that is not easily abandoned and certainly not in the context of Palestine. How might one achieve justice—redistributive justice, that is, rather than mere reconciliation—if political demands cannot be made in the name of the collectives (in this instance, Palestinians) who have suffered the displacement and violence of settler-colonialism? We might need to hold onto such binaries—even if only for a time and even as we recognize that what it means to be a “settler” does not remain stable over time—in order to decolonize the political in substantive rather than merely formal terms.

Fazil Moradi, “In search of decolonised political futures: Engaging Mahmood Mamdani's neither settler nor native,” Anthropological Theory (December 2023). ABSTRACT: This text offers a brief overview of the Special Issue on Mahmood Mamdani's book, Neither Settler Nor Native: The Making and Unmaking of Permanent Minorities (2020), and a reading of the contributions and of Mamdani's plea for the historic importance of epistemological revolution and of learning to imagine a community of survivors. My reading is mediated through an autobiographical critique of political modernity and ongoing state violence. I explore more deeply what Mamdani calls ‘settler autobiography’ and a community of survivors, other than a community of memory that is unified and homogenised. By turning to unauthorised autobiographies, the autobiographies of those subjected to colonialism as annihilatory violence, I take up Mamdani's call to rethink political violence and the possibility of living together as survivors in Iran as a ‘decolonised political community’. In order to do so I turn to memories of irredeemable destruction, displacement and incalculable losses that live on in our (my mother's and my) deferred autobiographies, alongside the epistemological revolution in Iran—Women. Life. Freedom.

ARTICLES

Hesham Sallam, “The Autocrat in Training: The Sisi Regime at 10,” Journal of Democracy (January 2024). ABSTRACT: A decade has passed since General Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi assumed the Egyptian presidency. His reign has been marked by autocratic trial-and-error governance and the prioritization of personal desires and instincts over the needs of the Egyptian people. Sisi's focus on state-led infrastructure projects, such as the building of new cities and a new Suez Canal, initially stimulated economic growth but masked underlying economic weaknesses. His military-centered economic strategy expanded the military's role in the economy, leading to a precarious autocracy heavily reliant on coercion and external support. Sisi's economic policies, marked by heavy borrowing and austerity measures, have disproportionately impacted low- and middle-class citizens, leading to rising poverty and social discontent. Despite attempts at economic reform, Sisi's governance remains characterized by personalist rule, resistance to formal institutions, and a reliance on repression to suppress dissent, leaving Egypt in a precarious economic and political state.

Ani Sarkissian and Ann Marie Wainscott, “Benign bureaucracies? Religious affairs ministries as institutions of political control,” Democratization (January 2024). ABSTRACT: Despite calls for examining how authoritarian regimes employ state structures to prolong their rule and evidence that they regulate religion to shape the behaviour of religious elites, there has been little attention devoted to religious affairs ministries, which are key sites of interaction between religious actors and the state, and are often the primary institution through which regimes manage religion. This study identifies and describes eight core areas these ministries regulate that can be used as instruments for repression and co-optation of regime opponents, and state legitimation: prayer, appointments, education, religious advice and decisions, religious endowments, media, registration, and charity. In this analysis, we seek to bridge the gap between the literatures on religion, the Middle East, and authoritarianism by synthesizing recent research and analysing religious affairs ministries in the Middle East-North Africa (MENA) region. We argue that by fulfilling these functions, religion ministries are not benign bureaucracies but impactful institutions of political control. In highlighting key questions that remain unanswered, we outline a research agenda for continued advances towards theorizing how authoritarian regimes might make use of state resources to protect their rule.

Mashuq Kurt, “Radical Habitus: Trajectories of Youth Radicalization in Turkey,” Current Anthropology (January 2024). ABSTRACT: This article investigates trajectories and sociopolitical drivers of youth radicalization in Turkey in the context of the Syrian war and the Kurdish national struggle. It proposes a conceptual framework (radical habitus) to better understand contemporary radicalization phenomena. Drawing on 18 months of ethnographic research, conducted between 2015 and 2018 in Turkish-Syrian border cities, in Istanbul, and in a refugee camp in Greece, I offer an anthropological intervention in the study of radicalization. Radicalization scholarship is often concerned with ideological factors and the immediate social circles of radicalized individuals while underplaying the macrolevel hegemonic forces that shape their lived reality and habitus. I argue that we must examine power relations, structural inequalities, perceived injustices, and young people’s political subjectivities in order to better understand what propels radicalization. I propose that radicalization is a relational and gradual process triggered by a set of complex power relations between state and substate actors across religious, sectarian, ethnonational, and class lines, the interactions of which shape what I call a radical habitus.

Heba Alnajada, ““This Camp Is Full of Hujaj!”: Claims to Land and the Built Environment in a Contested Palestinian Refugee Camp in Amman,” Comparative Studies in Society and History (January 2024). ABSTRACT: Historically, Islamic sharia courts across the Ottoman empire used a document called a hujja for registering property transactions. In present-day Jordan hujaj are illegal, yet in Palestinian refugee camps hujaj continue to be used for inheritance, buying and selling houses, and demonstrating occupancy. This is particularly true in camps unrecognized by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East and deemed “squatter settlements” by Jordanian host authorities. This article contributes to the emerging study of property rights in Palestinian camps by focusing on the links between Ottoman property regimes, contemporary territorial claims, and legal pluralism. Using the case of a Palestinian camp built on land owned by the descendants of Ottoman Circassian refugees, the article illustrates how, on the one hand, Palestinians use hujaj to facilitate inhabitation of the camp; and how, on the other hand, private property rights intersect with the competing claims of refugees and the state, whose overriding power changed after the events of Black September in 1970. By historicizing the material processes of refugee land tenure and property creation, the article challenges the assumption that contested camps are part of the “informal” growth of Middle Eastern cities, thus, bringing so-called squatter settlements back into refugee studies, Palestine studies, and Ottoman studies.