It's summer (at last). But the MENA Academy never rests.

Rethinking the Arab uprisings, and the latest academic journal articles.

Greetings, members of Abu Aardvark’s MENA Academy! Now that I’m back from a week’s travel to Uganda (for a Pasiri workshop at the Makrere Institute for Social Research about which you’ll be hearing more soon) via Doha (for reasons you’ll also hopefully be hearing about soon), it’s time for a few personal updates as we transition into summer. I will thankfully be on leave for the coming academic year, stepping down as director of the Elliott School’s Middle East Studies Program so that I can focus on raising baby Hazel (who’s doing great, I’m so thankful to report). I’m very grateful to the Mershon Center at Ohio State University for hosting me as a scholar in residence again next year.

The Middle East Political Science podcast and most POMEPS activities are heading into summer break, but keep sending me notices about books you’re publishing — the fall season will be upon us all too soon. Also, I’ll continue to run this blog — keep an eye out for my summer reading list and exploratory virtual book club! And finally, for those of you attending the 2024 APSA Annual Conference in Philadelphia, please join us at the POMEPS reception — co-sponsored again this year with the APSA’s MENA Politics Section. The reception is Friday, September 6th, 2024 from 7:30 pm to 9 pm at the Commonwealth C Room at the Loews Philadelphia Hotel. Hope to see you there — there’s a rumor that Hazel might even make an appearance!

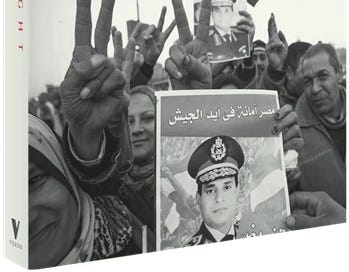

Book of the Week: Hugh Roberts’ Loved Egyptian Night: The Meaning of the Arab Spring (Verso, 2024). I had the pleasure of reading this new book on one of my flights last week. It collects and expands some of Roberts’ critical essays on the 2011 Arab uprisings and their aftermath, with a particular focus on Libya, Syria, and Egypt (where he was based during the revolution and its immediate aftermath). A longtime Crisis Group analyst and current Tufts professor, Roberts argues that none of the uprisings, save Tunisia’s, was actually a revolution, and that academics and journalists misinterpreting them as such had devastating analytical and policy consequences (several years into Kais Saied’s autogolpe and cascading repression, I wonder if he would even still put Tunisia into the revolutionary category).

Roberts revels in critiquing a wide range of books and authors (which may be an artefact of the origin of the essays in the New York Review of Books). I appreciate that he engages throughout with my two books on the topic (The Arab Uprising and The New Arab Wars), even where he criticizes them. I accept some of the criticisms (more attention to London and Paris may have been warranted), for others would defend my judgements based on the information available at the time or would continue to defend them now; this is how it should be, and I would just point back to my November 2014 essay where I engaged in some self-criticism and responded to some of those points.

Roberts is especially critical of the scholarship and media analysis of what happened in Egypt and Libya. In Egypt, he believes that the military played everyone expertly from the very beginning, using the young revolutionaries of Tahrir Square as a catspaw to maneuver the Mubaraks from power and seize back military domination from the Presidency and the National Democratic Party. Some of his observations about events and personalities make for uncomfortable and convincing reading for those who remember living through these events, while others may leave such observers unpersuaded. At times, he may project too much control and certainty to the military, portraying the steady unfolding of a master plan where there may have been a lot more unpredictability, uncertainty and gamesmanship than it appears in retrospect (particularly during 2011-12). But given Roberts’ analytical acuity and proximity to events, nobody should too easily dismiss his interpretations.

Probably the most controversial, and most interesting, part of the book revisits his longstanding arguments about the Libyan uprising and the NATO intervention. Roberts views much of the case for humanitarian intervention as either propaganda or else as an overly excitable reading of events. Based on his reading of decades of Libyan politics, Roberts rejects the argument that Qaddafi would have carried out a massacre of his opponents in Benghazi had NATO not intervened. He makes a strong and well-informed argument here, but ultimately I remain unconvinced. Given the seriousness of the threat to Qaddafi’s rule and his demonstrated willingness to use force, I think there was good reason to believe that such a massacre would have followed — and, even more, that policymakers and analysts watching the unfolding of events had good reason to be skeptical of such reassurances. It’s fascinating to read about the Crisis Group’s alternative policy proposals and to speculate about what might have been, and easy to understand Roberts’ frustration that those suggestions were not followed given Libya’s horrible post-intervention trajectory; that’s an all too familiar feeling to anyone who has ever offered policy recommendations and watched what happened instead.

It’s easy to be a skeptic about the Arab uprisings now, fourteen dismal years later. Roberts was a skeptic from the start. Agree or disagree with the arguments, Roberts has written a lively, contentious and thought-provoking rethinking of the 2011 uprisings which is worth the read.

And now, here’s the academic publications which jumped out at me last week. We lead with Liran Harsgor’s important short article on generational changes in Israeli political attitudes (spoiler: the young are more hawkish in Israel). Ora Szekely looks at women and the Syrian opposition. Kelsey Norman and Carrie Reiling look at Moroccan policy and the vulnerability of women in migration. Thomas Serres offers a fascinating take on the engagement of the Algerian disapora with the Hirak. Alexander Cooley, John Heathershaw, and Ricard Soares de Oliveira have a really important article on the rise of illiberal transnational networks which isn’t about the Middle East, but is totally about the Middle East. And finally, Waleed Hazbun introduces a special issue about the role of tourism in the evolution of the modern Middle East — fascinating historical perspectives with a theoretical payoff. Enjoy!

Liran Harsgor, “The young and the hawkish: Generational differences in conflict attitudes in Israel,” Research and Politics (May 2024). ABSTRACT: How do generational patterns affect public opinion in prolonged conflicts? While considerable research has addressed the effects of conflicts on children and adolescents, understanding the broader generational divides in public attitudes towards conflict resolution remains an area with both theoretical and empirical gaps. Such understanding is crucial, given its potential to significantly shape aggregate public opinion and the trajectory of conflicts. This paper focuses on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, examining how support for conflict resolution varies across Israeli–Jewish cohorts. It employs longitudinal survey data (1981–2019), using both descriptive methods and age-period-cohort (APC) regression models. The findings indicate that generational differences in public opinion were relatively small until the early 2000s. Post this period, younger Israelis have increasingly displayed more hawkish attitudes than older generations, coupled with a stronger inclination towards right-wing identification. These trends pose important questions about the changing nature of support for compromise within Israeli society and its implications for the future of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. The factors driving these emerging generational gaps are complex and merit in-depth exploration. While this article touches upon potential explanations, including demographic shifts and hope for peace, they do not entirely clarify the observed generational differences, highlighting the need for further research.

Ora Szekely, “Women’s engagement with the Syrian opposition: Pathways, perspectives, and participation,” International Political Science Review (May 2024). ABSTRACT: In its early months, the Syrian uprising included a diverse array of participants, including many from communities that the regime had previously assumed to be loyal, whether because of their sectarian identity, where they lived, or family ties to the military. The experiences of women from these communities can shed light on important aspects of the Syrian uprising, and test some of our key assumptions about women’s participation in contentious politics and the gendered aspects of political violence. Based on interviews, this article engages with the work on gender and conflict in examining family connections and political grievances that drew many women to the opposition, the specifically gendered risks that they faced, and the advantages that some women felt their gender and sectarian identities gave them as organizers and activists.

Kelsey Norman and Carrie Reiling, “The ‘inherent vulnerability’ of women on the move: A gendered analysis of Morocco’s migration reform,” Journal of Refugee Studies (May 2024). ABSTRACT: Beginning in the 1990s, Morocco increasingly became a de facto host country for sub-Saharan migrants and asylum seekers originally intending to reach Europe. While the government’s treatment toward these groups was characterized by informality and violence throughout the early 2000s, Morocco embarked on a reform process in 2013 that included a regularization process for irregular migrants. During the regularization process, the Moroccan government automatically granted all women applicants residency status due to their presumed ‘vulnerability’. This paper asks: What are the implications of assuming that women are ‘inherently vulnerable’? Drawing on in-person interviews and an analysis of policy documents, this article adds to the gendered migration and refugee literature by demonstrating that supposedly humanitarian policies toward women can also victimize them, stereotype male migrants and refugees as threatening, and strengthen the patriarchal role of the state and its ability to carry out violence in the name of protection.

Thomas Serres, “Diasporic Democratic Futures: The Algerian Hirak in Tunis, Paris and the Bay Area,” Middle East Critique (May 2024). ABSTRACT: The Algerian diaspora mobilized massively to support the 2019 peaceful uprising known as the Hirak. In so doing, Algerians from abroad contributed to collective performances of citizenship and civility that redefined political subjectivities in both their country of origin and their host country. This article studies the experience of activists based in Tunis, Paris and the Bay Area. Drawing on the works of theorists of radical democracy such as Chantal Mouffe and Bonnie Honig, it shows the way in which diasporic citizens supporting a revolutionary movement challenge traditional statehood and interrogates the limits of their subversive political practices. It emphasizes three aspects of this transnational mobilization: the contradictory dynamics of deterritorialization and reterritorialization, the constitution of agonistic arenas, and the emergence of new modes of subjectivation.

Alexander Cooley, John Heathershaw, and Ricard Soares de Oliveira, “Transnational uncivil society networks: kleptocracy’s global fightback against liberal activism,” European Journal of International Relations 30, 2 (June 2024). ABSTRACT: What is the global social context for the insertion of kleptocratic elites into the putatively liberal international order? Drawing on cases from our work on Eurasia and Africa, we sketch a concept of ‘transnational uncivil society’, which we contrast to ‘transnational activist networks’. While the latter denotes the liberalizing practices of global civil society, the former suggests a specific series of clientelistic relations across borders, which open space for uncivil elites. This distinction animates a growing line of conflict in global politics. These kleptocrats eject liberal activists from their own territories and create new spaces to whitewash their own reputations and build their own transnational networks. To do so, they hire political consultants and reputation managers, engage in public philanthropy and forge new relationships with major global institutions. We show how these strategies of reputation-laundering are neither illicit nor marginal, but very much a product of the actors, institutions and markets generated by the liberal international order. We compare and contrast the scope and purpose of civil and uncivil society networks, we explore the increasing globalization of Eurasian and African elites as a concerted strategy to distance themselves from associations with their political oppression and kleptocracy in their home countries, and recast themselves as productive and respected cosmopolitans.

Waleed Hazbun, “Tourism and the making of the modern Middle East,” Journal of Tourism History (May 2024). ABSTRACT: Since its inception the Journal of Tourism History has sought to expand the interdisciplinary field of tourism history to include scholarship from and about regions such as the Middle East. This special issue on ‘Tourism and the Making of the Modern Middle East’ is based on a conference sponsored by the Southeast Regional Middle East and Islamic Studies Society (SERMEISS) and held at the University of Alabama in 2022. While mostly focused on developments in Lebanon and Iraq before they gained independence from France and Britain, the essays explore how national actors used tourism to integrate populations within the newly formed political entities of the Mandate era into viable nation-states and to position these emerging states within the international framework defined by expanding tourism economies. Together these studies show how tourism and its impacts in the Middle East are multilayered, transnational processes within and across the emerging territorial nation-states of the region.