Maghreb Noir

A beautifully written new history of a pan-African revolutionary generation of artists

Summer’s the perfect time to dig in to that big pile of books that’s been stacking up through the end of the semester — so I’ve got a bunch of review essays for you in the coming days!

Paraska Tolan-Szkilnik, Maghreb Noir: The Militant Artists of North Africa and the Struggle for a Pan-African, Postcolonial Future (Stanford University Press, 2023)

If you’ve been following this blog you’ll know that I’ve been really interested the last few years in the transregional connections and the origins of the disconnections between North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa. Paraska Tolan-Szkilnik’s delightful Maghreb Noir makes a genuinely original and beautifully written contribution to this emerging area of study. Her careful reconstruction of the Maghreb Generation of pan-African artists, authors and poets positively sings with the electric energy of discovery. Tolan-Szkilnik sets out to reclaim postcolonial North Africa as a core site for postcolonial African militant activism, profiling both the official efforts of governments such as Algeria’s FLN and Tunisia’s Bourguiba to speak to a pan-African public and the unofficial counter-mobilization of militant artists and poets who rejected the encroaching authoritarianism of postcolonial regimes. It’s a veritable feast, full of sparkling character studies and reconstructions of forgotten historical moments. Anyone who shares my interest in the place of North Africa in pan-Africanism is going to want to read this one. (You can read her own introduction to the book here, if you still use the bird-site.)

Maghreb Noir focuses on what she calls the “Maghreb Generation” of militant artists and poets who built and populated a critical site of pan-African engagement in the 1960s and 1970s. Tolan-Szkilnik highlights the tension between competing visions of pan-Africanism, one state-sponsored and punctuated by major festivals and conferences and the other “state-skeptical.” The militant artists she profiles sought to build a revolutionary postcolonial pan-African culture from Algiers, Rabat and Tunis, with their magazines and films “dissenting from both the enduring legacies of European colonialism and the authoritarianism of the postcolonial states.” Senegal’s poet-President Leopold Senghor’s concept of negritude is a particular foil for the early wave of of this alternative critical generation.

The centering of these North African effectively decenters Europe, following the artists themselves, who engaged with French and European trends but were determined to speak to and about themselves on their own terms. But even more, it aims to challenge the artificial divide between North Africa and the rest of the continent, which has marginalized study of the Maghreb in African Studies and concealed the many connections and engagements which were taking place in those early years following decolonization. In those engagements, Blackness came to be seen in political rather than racial terms, bringing Arab and Amizagh - and even White - militants into a pan-African identity based on shared struggle against postcolonial repression and domination.

The centrality of Algiers for a certain revolutionary moment won’t come as much of a surprise — it wasn’t called the Mecca of Revolutionaries for nothing. But Maghreb Noir finds plenty new to say about this fascinating era, particularly the efforts of militant artists and poets to push back against the official Algerian government’s efforts to take leadership via events such as the 1969 PANAF (Pan-African Festival of Algiers). Her sketch of the poet Jean Sénac - “a poet, a socialist with an anarchist sense of humor, a lapsed Christian, a homosexual, and above all a prolific writer who penned words on any material he could find — bus tickets, toilet paper, and city walls included” — serves as a showcase for her historiographical method and brilliant prose (we can all hope to deserve such a one line biography someday). She documents how Sénac consistently strove to “tighten links between Africa and the Arab world”, first in collaboration with the Algerian regime and soon enough (by the early 1970s) in frustrated opposition; he was ignored by the official historians of the PANAF and assassinated in the summer of 1973.

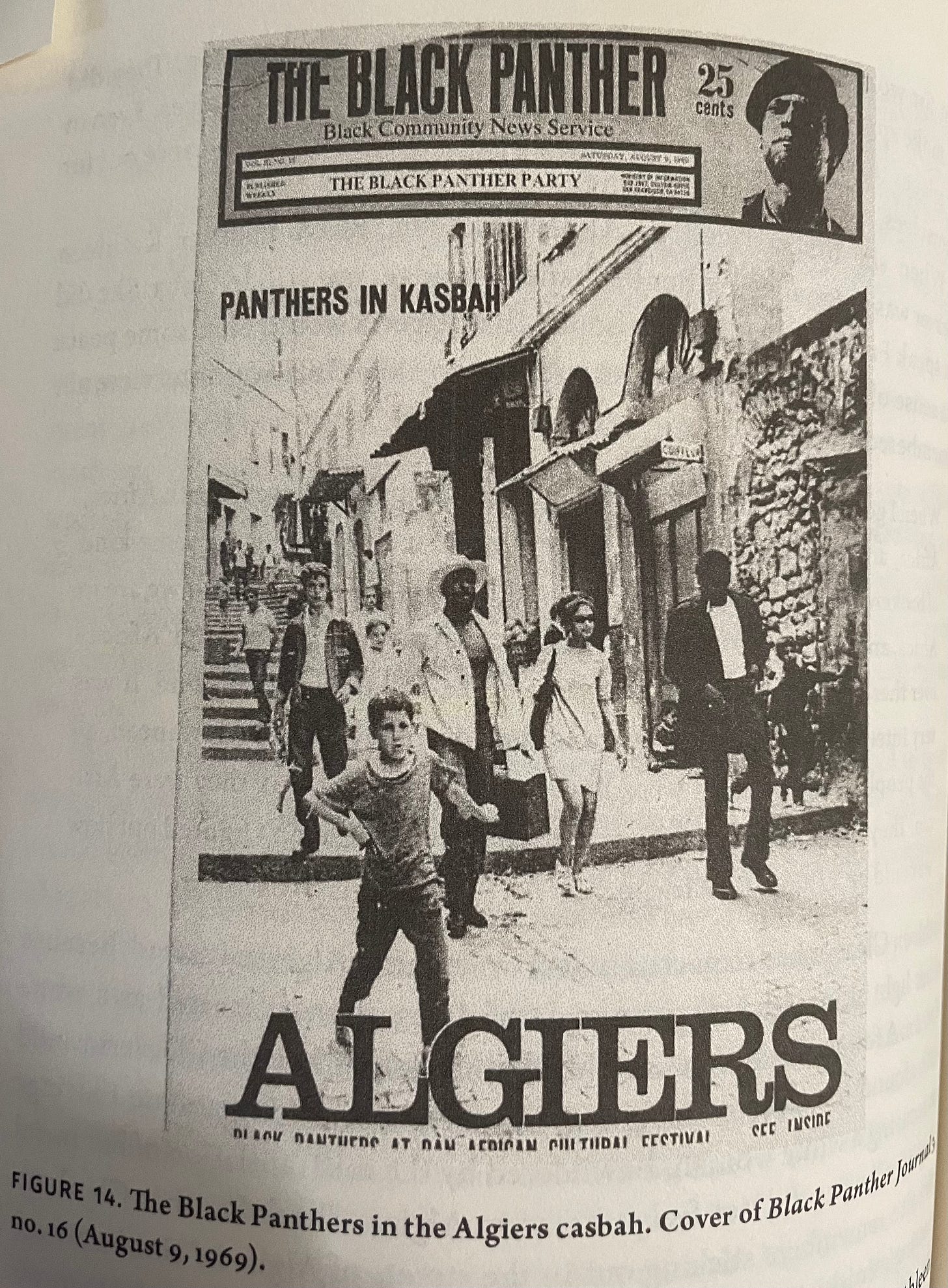

Her chapters on the Black Panthers in Algiers (the above image of Black Panthers in Algiers is one of the many wonderful finds she includes in the book) and on the role of women in all of this revolutionary artistic convening are simply jaw-dropping; I found myself reading passages aloud to friends often enough that they are probably glad that I’ve finished the book. Her interviewees repeatedly, without prompting, brought up their sexual conquests and adventures - “they almost exclusively framed this struggle [for women’s liberation] in terms of sexual liberation, concerned with liberating women’s bodies from the oppression of colonial chastity.” Race and sex intersected in uncomfortable ways in these recollections: “In the end, the men of the Maghreb Generation created a community premised on revolutionary masculinity, casting women as ahistorical and apolitical symbols of Africa to conquer and collect through sex.” Um. Well then.

The place of Rabat and Tunis in pan-Africanist cultural struggles is less well-known than that of Algiers. Tolan-Szkilnik devotes several chapters each to these cities, restoring them to their place in the evolution of pan-Africanism. She sees Rabat as a pivotal, vibrant and multicultural crossroads in the early years, highlighting the movement of intellectuals and revolutionaries between Paris and Rabat in the years before Algeria won its independence in 1962. Angolan activists were particularly prominent, a connection which I found both logical and fascinating. Rabat’s role began to fade with the ascension of Hassan II to the throne, as he turned towards the West and against pan-African revolution. For Tunis, she highlights the latter half of the 1960s, when Bourguiba shifted from emphasizing Middle Eastern issues such as Palestine to a bid for African leadership highlighted by a month-long trip to eight West African states. On the artistic front, these chapters focus on a generation of revolutionary African film-makers centered in Tunis and their repeated tensions with the regime’s propagandistic preferences.

Maghreb Noir is a rich, highly original, and beautifully written contribution to our understanding of pan-Africanism and the Maghreb. I thoroughly enjoyed it, and would definitely encourage putting it on your summer reading list if you’re interested in any of those topics - or even if you aren’t.