Necropolitics in Syria and Gaza

A theoretically rich book on the logic of violence applies all too well today. That, plus this week's MENA Academy roundup.

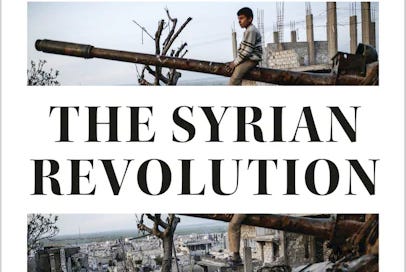

Yasser Munif, The Syrian Revolution: Between the Politics of Life and the Geopolitics of Death (Pluto Press, 2020).

Indiscriminate bombing and airstrikes which kill disproportionate numbers of civilians, women and children. Destroying hospitals and schools. Siege tactics to weaken and starve targeted populations, while encouraging the spread of contagious disease and debilitating the health care and water purification infrastructure. Mass dispossession of populations associated with hostile ethnic or religious groups. The absence of a clear strategy for victory beyond the seemingly boundless killing. All of these military tactics clearly violate the laws of war, and should be roundly condemned — and perpetrators held accountable, regardless of the provocation — but the regime is protected by a great power patron with a Security Council veto.

Did you read that paragraph and immediately think Israel’s war on Gaza? You should. But it actually refers to Syria’s civil war and the strategies of violence employed by the regime of Bashar al-Asad — about whose war criminal credentials few would disagree. Harun Rashid’s fascinating 2020 book The Syrian Revolution (which isn’t new, but I only read recently) draws on Cameroonian political theorist Achilles Mbembe’s concept of “necropolitics” to place violence in all its forms at the heart of the Syrian regime’s survival strategy — and to address a range of puzzles about where, when and how violence has been deployed. His insights apply widely beyond Syria — and match all too well what Israel has done to Gaza.

There have been a lot of important works on the logic of regime violence in Syria’s war, including Kevin Mazur’s detailed analysis of the first year of the war, Revolution in Syria, Samer Abboud’s Syria, Salwa Ismail’s formidable The Rule of Violence, and Yassin al-Hajj Saleh’s The Impossible Revolution. Munif’s stands out by grounding its analysis of violence in Fanon and Mbembe — with the latter’s concept of Necropolitics especially relevant to making horrifying sense of regime violence in particular.

By starting from an account rooted in Africa’s postcolonial wars and autocracies via Fanon and Mbembe, Munif avoids being seduced by the particularism of a case or by the tropes of Middle East regional analysis. The hard logic of the manipulation and exercise of violence in all its forms — from direct action to the less visible forms of killing such as spreading disease and preventing the operation of relief agencies or doctors — can not be isolated to the unique pathologies of singular cases such as Asad’s Syria or Saddam’s Iraq. As Mbembe puts it, “nearly everywhere the political order is reconstituting itself as a form of organization for death… a terror that is molecular in essence and allegedly defensive is seeking legitimation by blurring the relations between violence, murder, and the law.” Israel’s policy in Gaza — and not only those taken after October 7 — is among the more brutally evocative avatars of necropolitics the world has seen. Declaring analysis or reporting of the violence in Gaza off-limits, or insisting on some unique or exceptionalist grace for understanding its motivations or intentions, doesn’t make those realities go away.

My own research these days is very much influenced by the theoretical challenges in confronting the constitutive centrality of violence that Mbembe poses, by the difficulties and necessities of comparison between Middle Eastern warscapes and those of Africa and other postcolonial areas, and by the profound urgency of accounting for what has been done, and is being done continuously, to the people of Gaza. We should be as insistent on documenting, theorizing, and calling for accountability for the violence inflicted on Gaza as we rightly were in Syria, in Iraq, in Afghanistan, in Yemen, in Darfur, in Ukraine, or in any of the other all too many areas where necropolitics have taken hold. Munif’s The Syrian Revolution is a good introduction to this mode of thinking and analysis; there is far more to be done.

And now for this week’s MENA Academy. I look forward to seeing at least some of you at APSA in Philadelphia this week. I am hosting the POMEPS reception at the Loewe’s International at 7:30 Friday night, so definitely stop by there if you want to see me; otherwise, I will be around the book room Saturday afternoon, so if you want to meet up message me in advance or stop me if you seen me.

This week’s roundup from the journals features another set of articles with connections to POMEPS, including an innovative and rigorous example of how to use social media for causal analysis, an excellent analysis of Jordanian protest activity, and a review of the literature on negotiations with jihadist insurgent. Enjoy!

Anita Gohdes and Zachary Steinert-Threlkeld, “Civilian behavior on social media during civil war,” American Journal of Political Science (September 2024). ABSTRACT: Recent research emphasizes social media's potential for citizens to express shared grievances. In active conflict, however, social media posts indicating political loyalties can pose severe risks to civilians. We develop a theory that explains how civilians modify their online behavior as part of efforts to improve their security during conflict. After major changes in territorial control, civilians should be more likely to post positive content, and more content that supports the winning side. We study social media behavior during and after the siege of Aleppo in November 2016. We match Aleppo-based Twitter users with users from other parts of Syria and use large language models to analyze changes in online behavior after the regime's retaking of the city. Results show that users in Aleppo post more positive and pro-Assad content, but only when self-disclosing their location. The findings have important implications for our understanding of digital communication in civil conflict.

Matthew Lacouture, “Claiming a “Right” to State Space: Building Social Movements Under Authoritarian Rule,” Comparative Political Studies (September 2024). ABSTRACT: There is widespread agreement in social movement research that successful mobilization requires gatheringlarge numbers in public spaces. But what happens when repressive states close public spaces off to protests and activists lack the capacity to win them from state control? This article utilizes a case study of state workers’ movements in Jordan in the run-up to the 2011 uprisings to demonstrate how activists can mobilize under repressive conditions by seeking out less conventional spaces. Specifically, workers may be able to access state spaces associated with public employment (e.g., state ministries and public schools). I argue that these spaces can serve as sheltering spaces for protestors to engage in early movement-building activities and as performative spaces to generate political support needed to expand into more exposed spaces. Overall, this research contributes to understanding contentious politics in politically repressive settings by identifying a middle ground between covert resistance and mass public demonstrations.

Dino Krause, “Negotiating Peace with Islamists? Reviewing the Literature,” Terrorism & Political Violence (September 2024). ABSTRACT: Armed conflicts with Islamist non-state groups appear particularly resilient against peace negotiations, while existing research on the subject remains scarce and scattered across different sub-literatures. This study provides the first systematic literature review to identify explanations for the challenges that Islamist conflicts pose for peace negotiations. Gathering theoretical arguments and empirical findings from a total of 57 studies published between 2001–2024, the analysis yields important insights. On the one hand, it shows that existing explanations focus on the Islamists’ ideology, their often cell-like internal structure and access to transnational support channels as potential barriers to negotiation onset. On the other hand, responsibility is also ascribed to governments, highlighting their tendency to overlook potentially negotiable grievances held by Islamists, the acting of external governments as veto players and the proliferation of terrorist-listings as hurdles for conflict resolution. At the same time, the reviewed studies suffer from limitations with respect to the external validity of the obtained findings. Moreover, some of the identified explanations are primarily raised in studies of transnational Islamist groups but remain largely absent from studies dealing with nationally focused Islamists. Based on the obtained findings, I propose several suggestions for future research.