Racializing Islam in Algeria

My weekly review essay looks at Muriam Haleh Davis’s new book on French colonial developmental racial formations

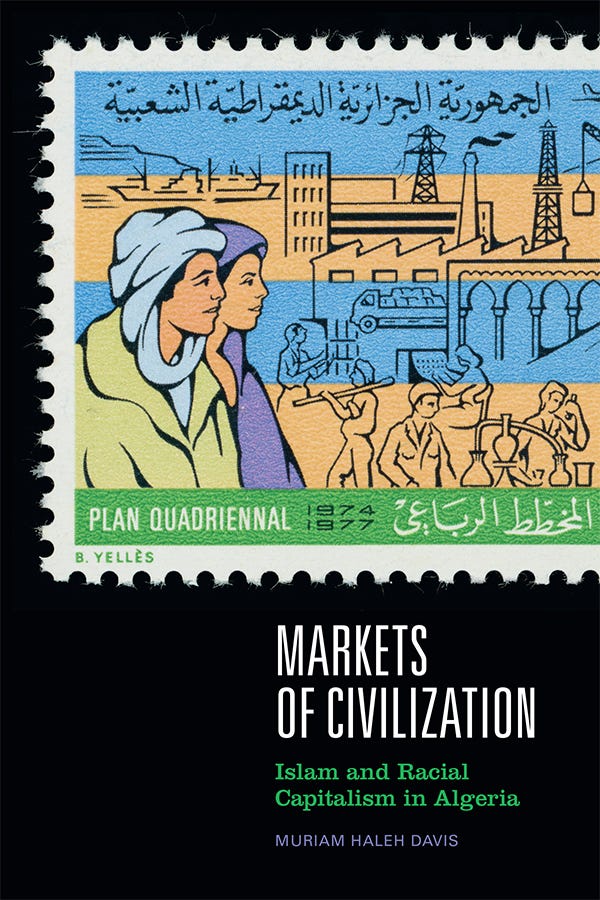

Muriam Haleh Davis, Markets of Civilization: Islam and Racial Capitalism in Algeria (Duke University Press, 2022).

Muriam Haleh Davis contributed an especially fascinating essay to last year’s stellar special issue on the “Cultural Constructions of Race and Racism in the Middle East and North Africa / Southwest Asia and North Africa.” Focused on Frantz Fanon, Davis “drew on his analysis of anti-Black racism in mainland France to understand the dynamics of settler colonialism in Algeria.” My recollection of that great piece was triggered last week by her new essay in the LA Review of Books, a provocative argument against those studies which appropriated Fanon for the study of Blackness in the United States while stripping away the context of the Algerian revolution and global decolonization struggles. That essay in turn alerted me to the September publication of her new book, Markets of Civilization: Islam and Racial Capitalism in Algeria. Which is to say, I obviously had to read it.

Markets of Civilization fits neatly with the pairing of books by Abdelmajid Hannoum and Megan Brown in my review essay this past May. Where Hannoum examined the French construction of an ontologically distinct Maghreb rooted in racial categorizations, and Brown focused upon post-independence Algeria’s uneasy place within the emergent European Economic Community, Davis hones in on the fascinating connections between French economic development plans and the racialization of Islam. She argues convincingly that the distinctive racial formations of French Algeria have had enduring effects on the political economy of Algerian identity politics. It resonates nicely with Jennifer Sessions’ brillian decade old book By Sword and By Plow taking the French encounter with the Algerian peasantry (such as it was) in a quite different direction. Basically, I’m of the opinion that there can never be enough books about Algeria, for a multitude of reasons.

Racial difference was obviously built in to the settler colonialism of French Algeria from the start, but the terms of the racial formation were not always obvious. The divide between Black Africa and the Maghreb in French colonial practice problematized reliance on skin color, while the large scale European Christian settlers, the indigenous Jewish population, and the discourse around a “less Islamic” Berber population pointed towards religion as the defining line. Where skin color typically marked that divide in colonial Africa, in Algeria Islam instead became “the basis of a racial regime of religion which underpinned the economic structures of the settler colony.”

Islam here didn’t just represent ideas or theology; its racialization in economic and political practice by French Algeria shaped “discriminatory patterns of access to life, livelihood and property.” Davis tracks the shift after World War II from biological racism to a racial distinction based on attributed cultural characteristics in economic and developmental thought. As France contemplated economic development policies which might drain support for the emergent Algerian revolution, they converged on notions rooted in a long history of Orientalist study and colonial practice. In this telling - familiar from Timothy Mitchell’s observations of colonial Egypt - the key distinction between Europeans and “native” Algerians resided in economic orientations towards modernity, with native Algerians innately antimodern for reasons derived from Islam. Racialized tropes familiar from other colonial contexts were here assigned based on religion rather than skin color: “the ability of Europeans to recognize allegedly universal interests was defined against the inability of colonized subjects to embody the values of economic modernity.”

That development now required cultural transformation, teaching Algerian Muslims to set aside the cultural ethos of homo islamicus and learn the market-oriented ways of the European homo economicus (it’s difficult to not hear a lot of this as modernization theory rendered in French). It is the racialization of these ideas which sets the French practice in Algeria apart: “On the basis of religion, Muslims in Algeria were disproportionately subjected to racism.” European settlers, by contrast, “gradually came to occupy a position of structural whiteness,” defined by social, legal and economic privileges (and immunity to colonial state violence) rooted in the personal status law.

Markets of Civilization does not stay at the level of theoretical abstraction or discourses on race. Much of the book digs deep into the details of economic planning and development projects, especially in the late French colonial period and in the early postcolonial independent Algeria. An especially fascinating extended vignette makes the racialized market conretely real by tracing the vagaries of the production of wine and olive oil: the former oriented to the market demands of export to Europe, the latter rooted in highly local tastes and styles of production which proved resistant to the standardizing imperatives of export markets. The book hinges around the Constantine Plan, formulated under de Gaulle partly in hopes of draining the economic grievances presumably fueling support for the FLN but also in hopes that it “would give rise to a symbiotic economic relationship after independence.” That meant cultivating a market ethos and practice among Algerian Muslims believed to be innately incapable of such an orientation: “the racial hierarchies constructed through colonization were embedded - though disavowed - in the Constantine Plan, which defined humanity in terms of market capacities and enterpreneurial activities.”

Davis places Algeria “within larger discussions about racial capitalism that expose how understandings of human difference determined which kinds of bodies would be subjected to extraction, violence, and legal exception.” She argues for the urgency of understanding “Algeria’s status as a settler colony and the need to remain attentive to specific racial formations.” The racialization of Islam through French development planning presents a fascinating case study of forms of racialization in which “religion - not skin color - served as the basis for legal exclusion and economic precarity.” Davis notes that this transformation of Islam into a marker of racial difference wasn’t inevitable, and wasn’t even replicated elsewhere in French Africa - in Senegal, for instance, Africans were allowed to retain both Muslim personal status and French citizenship.

The tension between this racial formation based on religion and racial formations based on Blackness created complexities for revolutionary and post-colonial Algeria. Despite pan-Arab enthusiasm for the Algerian revolution, the FLN, and especially the first post-independence President Ben Bella, centered independent Algeria’s revolutionary identity around Islam, in part to overcome “the racial legacies of French empire [that] had defined a ‘white’ North Africa in contrast to a ‘black’ sub-Saharan Africa, while also isolating Algeria from the eastern Mediterranean.” Davis notes late in the book how Algerian political thinkers differentiated themselves from Black Africa as they struggled to place their revolution within the currents of pan-Arabism, pan-Africanism, and Third Worldism - in part because of attitudes towards Blackness and racial difference internalized from the French colonial era.

As an aside, the cast of major intellectual figures who spent significant time in French Algeria always amazes me. Davis points out the 1882 arrival of Karl Marx, hoping to convalesce from a lung condition. Alexis de Tocqueville shows up in 1841 to dismiss the prospects of racial fusion in Algeria between Europeans and “savage and ignorant” Arabs. Fernand Braudel emerged from a decade of teaching secondary school in Algiers to lament Algeria as a “failed Brazil” because of “the emergence of rigid racial categories.” Pierre Bourdieu obviously looms large, as his studies of the Algerian peasantry both informed colonial practice and shaped his broader social theory. Classical Orientalists such as Jacques Berque and Ernst Renan appear amidst the intense debates over the applicability of theories of economic development to Muslim Algerians. Albert Camus appears too, briefly, pushing alternative concepts of Mediterranean hybridity. And so, too, does Fanon, very much cast within the historical specificity upon which Davis insists.

Markets of Civilization makes for a fascinating addition both to the literature on Algeria and also to the broader literature on racial formations and racialization. It’s a real strength of the book that she consistently engages with the latter literature, placing decolonizing Algeria directly into conversation with debates over Blackness from the United States to Africa. Her close analysis of Algeria’s particularities within these broader discourses redeems the arguments which framed her article on Fanon which led me to seek out the book in the first place. Well worth the read, and a welcome addition to the literature.

This post is part of my series of weekly book review essays. Keep an eye out every Monday (more or less) for a new review essay about books about the Middle East and North Africa!