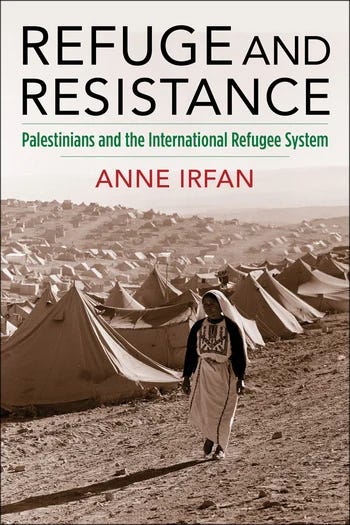

Refuge and Resistance

A regrettably timely new history of Palestinians and the international refugee system

The weekly MENA Academy book review essay returns today after last week’s interruption. Keep an eye out for the return of our regular MENA Academy research roundup next week, as well. Finally, I hope to have a follow-up post to the various debates and questions triggered by my policy writing on Gaza and Israel over the last week; look for that later this week.

Anne Irfan, Refuge and Resistance: Palestinians and the International Refugee System (Columbia University Press, 2023)

In the midst of unprecedented closures and a devastating bombing campaign following the October 7 Hamas attack, Israel instructed Palestinians in northern Gaza to leave their homes and head south to avoid bombardment and an impending ground invasion. The United States has been attempting to broker an agreement with Egypt to open the Rafah border crossing to fleeing civilians and allow them to seek shelter in a Sinai safe haven during the fighting. Most Palestinians in Gaza are desperate to avoid the devastating military onslaught, but fear that any such departure would be permanent, no matter what commitments Israel offers about their post-fighting return. Many view the assault on Gaza, in conjunction with the ever escalating settler attacks on Palestinian land and residents in the West Bank, as part of another Nakba, the 1948 flight of some 750,000 Palestinians who became permanent refugees. Both Jordan and Egypt have thus far absolutely resisted accepting any Gazans as refugees, similarly for fear based on experience that the temporary would again become permanent.

Anne Irfan, in her regrettably timely new Columbia University Press book Refuge and Resistance, explores the conditions under which those refugees built new lives in the camps of Jordan (at the time including the West Bank), Gaza, Lebanon and Syria. Refuge and Resistance is one of the first documentary histories of UNRWA, the UN agency responsible for the Palestinian refugees; Irfan got rare access to UNRWA’s Central Registry archive in Amman. She supplements the archives with interviews, memoirs, and a wealth of other sources to craft a riveting historical overview of the lives and experiences of Palestinians in the UNRWA camps. Irfan shows how Palestinian refugees stood outside the post-World War II international regimes governing refugees and how they actively negotiated the conditions in the camps over the span of more than half a century. It should be required reading for those today who blithely float ideas of Gazans temporarily seeking shelter across the Egyptian border or of Arab states accepting a new wave of Gazan refugees. There is, as they say, a history here.

UNRWA, as Irfan explains, quickly evolved from an emergency relief operation amidst tremendous confusion and hardship into a quasi-state entity governing hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees across multiple countries. It became more than an aid agency, she writes, “evolving into an extensive and complex system that operates across international borders and rivals the scope of national governments in places.” As the administrator of the camps, UNRWA took the place of the host states in providing education, health care, and municipal services. As it took on this role, UNRWA had to consistently grapple with the Palestinian refugees themselves, who frequently exercised their agency and made their preferences known over such issues of everyday life. That role evolved over the years as exile and refugee status continued, with generations born into the camps who had never known any other life and who gained entirely new political horizons and expectations.

One of the implications of the UNRWA “quasi-state” is that Palestinian refugees faced what she calls a “protection gap.” UNRWA had quasi-state like features, but it was not a state. It did not have the security or military powers to defend Palestinians. It had the unique property of having responsibility for the only group of refugees in the world which were not registered with or under the protection of UNHCR, and who stood outside of its protections and funding streams. It could provide identification cards, but not citizenship or legal status. Nor could it operate independently of the UN which authorized and funded it, weakness that episodically became a particular issue during political efforts by the US, Israel or others to defund the agency (as the Trump administration attempted in 2018). But it did become the primary point of access for Palestinian refugees to exercise their voice, a locus of mobilization and identity which helped shape generations of Palestinians in exile.

Irfan’s book roams through the various historical phases of the evolution of UNRWA and Palestinian life in exile. Early chapters, drawing on a wide range of primary documents, capture the trauma, shame and extremity of the Palestinian disposession and the extreme difficulty of the early refugee encampments. She offers a fascinating diplomatic history of the creation of UNRWA in May 1950 in the face of global recognition of those extreme hardships, particularly as it became clear that the newly created state of Israel had no intention of allowing the refugees to return. Critically, she documents the hostility many Palestinians felt to their benefactors because of their fears that UNRWA was conspiring with Israel and the West to improve their lives in order to reduce pressure for their return, and the intense fears among both Palestinian refugees and their hosts that UNRWA meant to encourage resettlement (tawtin). Their fierce hostility to any form of permanent resettlement is critical to understanding the physical and social geography of today’s camps. So too is the severe treatment of Palestinian refugees at various points in the history of Syria, Lebanon and Jordan — to say nothing of post-1967 Israeli control.

Much of Irfan’s narrative is taken up with demonstrating the agency of these stateless refugees, the many ways in which they pressed demands upon UNRWA and sought to shape their own conditions. For just one of many examples, she quotes from a 1951 report to the UNGA: “There have been demonstrations over the census operation, strikes against the medical and welfare services, strikes for cash payments instead of relief, strikes against making any improvements such as school buildings in camps in case this might mean permanent resettlement….” This was not a passive population, not from the very start and not in the later eras.

One of the most fascinating dynamics Irfan dissects in this early period is the move by UNRWA to shift its programmatic and developmental focus to education. She argues that this shift came in response to demands by the refugees, who wanted educated children who could seek a better life rather than material improvements which might increase the risk of resettlement. She describes education as “intrinsically tied to Palestinian liberation… the polar opposite of the hated ‘reintegration’ schemes.” That focus on education also helped to crystallize Palestinian identity across the far flung camps. Those camps, she notes, had a complex impact on that identity: “the camps demarcation enabled the host governments to treat them as sites of control, but it also enabled the refugees to retain the feeling of a national community in exile.” As those refugees worked to retain their identity and cultural practices, the identity category of “Palestinian refugee” took hold in new ways.

In later chapters, Irfan turns to the rise of the PLO and the post-1967 politicization of the camps and the grim realities of the political and military responses. The dark days of 1970s Black September in Jordan and the horrors inflicted on Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon in the 1970s and 1980s make for difficult reading. It also posed serious problems to UNRWA as a UN agency caught between politically mobilized militant factions, hostile local populations and regimes, and international pressure to maintain control. She draws on a wealth of documents and other sources to show how UNRWA was forced to navigate those tensions, including the demands from the UN and its major donor states as well as pressures from the host states and activism by Palestinians demanding that it advocate for their cause.

The horrors of the ongoing onslaught against Gaza and the pressures on its people to flee to some safe haven across the border has all too many echoes in these pages. Irfan describes Israel’s policy in the late 1960s as seeking “to reduce the Strip’s refugee population by permanently resettling as many of them possible elsewhere.” She catalogs its many efforts in that regard, including ofgering incentives to leave and keeping standards of living low, expulsions, and breaking up refugee camps and moving refugees to new encampments. Those who left, of course, were not allowed to return — which is the relevant backdrop to today’s reticence to leave even under the ferocity of Israel’s war machine.