Saudi oil cuts and American international order

Why the OPEC+ slashing of oil production has triggered the most intense crisis in the alliance yet.

“What Saudi Arabia did to help Putin continue to wage his despicable, vicious war against Ukraine will long be remembered.” - Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer

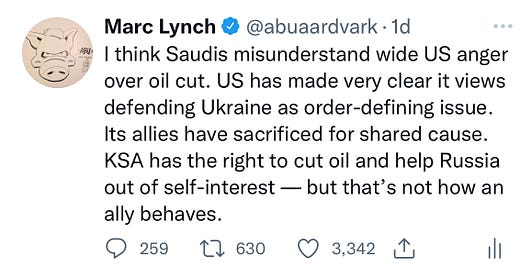

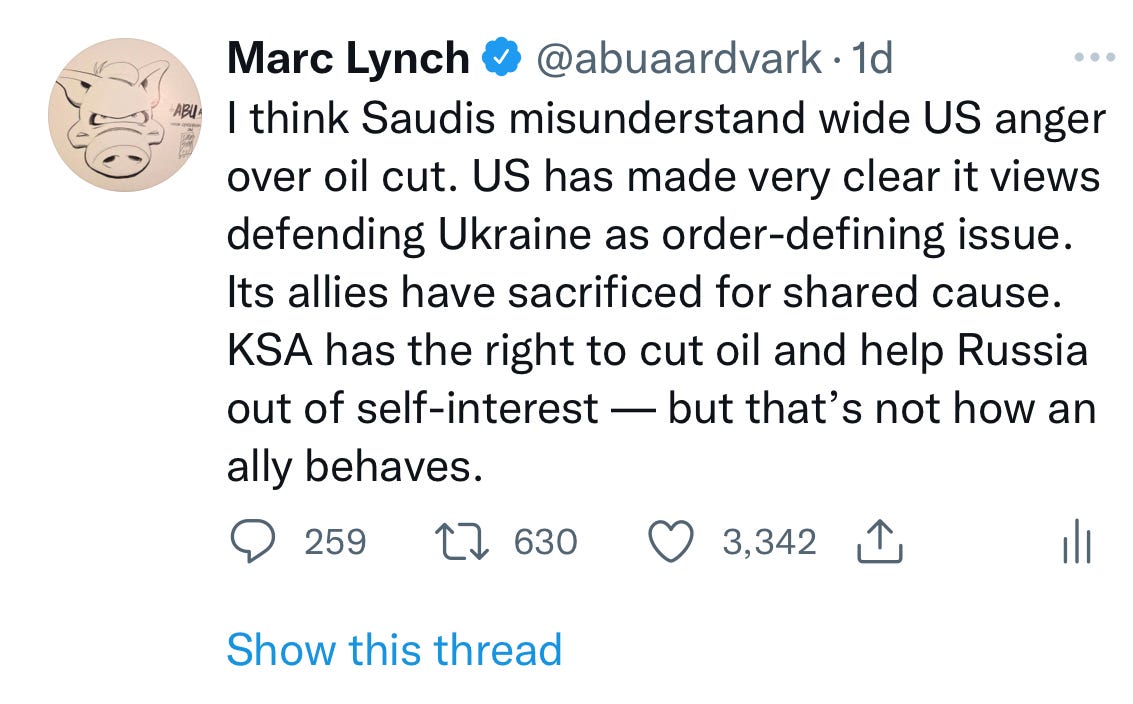

Saudi Arabia’s decision with OPEC+ last week to slash oil production by 2 million bpd has triggered perhaps the harshest backlash in the U.S. and Europe in memory.My tweet about it on Saturday has generated quite a lot of discussion which I’ve been watching play out with interest. The many vocal Saudi defenders of the decision have given an excellent window into their worldview and grievances with the U.S. I value their perspectives (mostly), though I’m not really the person they need to convince - they should be looking at the heated statements by a remarkable number of senior Congressmen and Senators, White House officials, and leading figures in the foreign policy establishment who usually defend the U.S.-Saudi alliance.

The Saudi arguments are mostly familiar - that the Gulf doesn’t take orders from the U.S. anymore, that it’s just about oil markets and not politics, that the U.S. failed to defend it against Iranian attack, that the US release of the Strategic Petroleum Reserve was the first shot. And that’s the problem. Those well-rehearsed arguments are rooted in more than a decade of stress in the bilateral relationship. Some of those arguments have merit, others don’t, but almost all of them miss the degree to which the game has changed from Washington’s perspective, as bilateral issues have been elevated to a much bigger debate about international order.

The United States and Europe view the collective defense of Ukraine from Russia’s invasion as an international order defining event, a generational moment in which international alliances and norms are being reshaped in real time. The Biden administration rallied an international coalition against considerable odds in support of Ukraine. That collective effort has become a defining signal of identity, of who’s part of the team and who’s not. Saudi Arabia (like the UAE and others) hedged from the start. Biden’s misconceived trip to Saudi Arabia and fist bump with MBS actually wasn’t just about oil prices, though that was of course part of it; it was, at a deeper level, an attempt to pull Riyadh back into the Western alliance. The intense response to the OPEC+ decision, which benefits a beleagured Russia while hurting both the United States and European countries facing a cold winter, came because it decisively places Saudi Arabia on the other side of what Washington sees as the key dividing line in world politics.

Part of the problem may be that the lack of clarity about what that dividing line actually was. The initial discourse defining it as democracies against autocracies was unfortunate, since Saudi Arabia and the UAE obviously didn’t fit with the former. Sure, there were those who attempted to drag out the old Arab exception, arguing that useful autocracies should be included on the team because at least they were supporting rather than challenging the status quo. But that too was awkward, given years of Saudi grievances with the U.S., strategic partnership agreements with China, and OPEC+ coordination with Russia — all based on their reading of an emergent multipolarity and their deepening doubts about American commitment to their security and long-term staying power in the Middle East.

The divide between the U.S. and Saudi Arabia has been a long time coming, of course. I’m among those who have long been critical of the alliance. My 2016 book The New Arab Wars argued that Saudi behavior since at least the Arab uprisings clearly demonstrated that it was not a real American ally. The murder of Jamal Khashoggi, the war on Yemen, and the various adventures of MBS further strained the alliance on the American side; nuclear negotiations with Iran, hostility towards MBS and the non-response to the attack on the Abqaiq oil refinery strained it on the Saudi side. The JCPOA and broader policies towards Iran loomed large on both sides.

All of those grievances are reinforced by domestic politics on both sides. Khashoggi and Yemen made Saudi Arabia an ever more central litmus test among Democrats, who resented the close relationship between MBS and Trump (via Jared Kushner) and openly believe that the Saudis were intervening in American politics on behalf of Republicans. Saudis, meanwhile, are infused by a combative new nationalism carefully cultivated by MBS’s team which views Americans as condescending and trapped in a patron-client past which no longer exists. I wonder if this aggressive public posturing will create audience costs on both sides which will make it harder to back down if cooler heads decide to try to preserve the alliance (the remarkable ease with which Saudis and Emiratis switched from demonizing Qatar to celebrating it when policy changed suggests that it probably won’t on the Saudi side, at least, but still).

This isn’t the first time there’s been intense criticism on both sides - see Victor McFarland’s lively and excellent 2020 Oil Powers: A History of the U.S.-Saudi Alliance (Columbia University Press) for a recounting of some of the highlights. But there’s a real sense that things are different this time. Earlier spats happened either during the Cold War, when the Saudis and Americans were mostly bound together by anti-Communist policy views, or during the era of American primacy, where Riyadh really had nowhere else to go. But the days of a unipolar America are long gone in the Middle East — fatally wounded by the American invasion of Iraq, made manifest by the 2011 Arab uprisings. The rise of Chinese investments and influence and Russia’s opportunistic interventionism give the Gulf states options, though the prospects of an actual break with the U.S. may shine a harsh light on those alternatives.

One of the counterintuitive implications of that semi-multipolarity is that intra-alliance politics carry higher costs. It’s one thing to threaten to break an alliance when everyone knows it’s not a real option, easily dismissed as cheap talk or performance for domestic audiences. It’s something else when the break might actually be conceivable. Even last decade, at the most heated days of Gulf complaints about the nuclear negotiations with Iran, there was a general sense that this was mostly intra-alliance bargaining, complaints that could be met with new arms deals or security guarantees or a green light to intervene in Yemen. It’s not obvious that this can work with Saudi Arabia acting on behalf of Russia at a moment when the United States has defined opposition to Russia’s invasion of Ukrainse as the defining line in international order.

Most people on both sides likely expect that everyone will eventually calm down, pragmatic concessions will quietly be made, and the alliance will go back to normal with another layer of negative residue corroding still strong foundations. That’s probably what will happen. But this one has a really different feel to it on both sides, and neither side should take it for granted.