The Political Science of the Middle East

Our new book presents the state of the art as seen by nearly fifty authors

Marc Lynch, Jillian Schwedler and Sean Yom, eds., The Political Science of the Middle East: Theory and Research Since the Arab Uprisings. Oxford University Press, 2022.

The Arab uprisings generated a tremendous amount of academic research. The sudden eruption of mass mobilization across multiple countries, with divergent outcomes across so many cases, presented political scientists with a vast range of new questions, cases, and data. For a brief time, at least, the long-marginalized Middle East community grabbed the interest of the “mainstream” of the field. How did the field do with these opportunities? Jillian Schwedler, Sean Yom and I have been working for years with a group of nearly fifty authors to answer that question, assess the field of Middle East political science, and point towards possible future directions. The fruits of this massive collaborative exercise have now been published by Oxford University Press as The Political Science of the Middle East: get a 30% discount from Oxford using the code ASFLYQ6. Or, if you can’t wait, the Kindle version is currently available and on sale for only $9.99.

We began this project with the idea that ten years after the uprisings offered a good opportunity to step back from the day to day political developments and get a broader view of both the region and the scholarship on the region. Such perspective is really important. Some early analytical conclusions looked robust at the time, but have since lost their luster. For instance, an early wave of research saw Egypt’s uprising and transition as successful, the wall of fear forever shattered; since the 2013 coup and fierce repression which has followed, Egypt looks much different. The variation of Egypt’s “failure” and Tunisia’s “success” inspired a subsequent wave of research; with Kais Saied’s coup against democracy, Tunisia no longer looks quite so successful. In the early part of the decade, it looked like certain countries which had recently experienced civil war were among the few which did not experience massive popular uprisings; it no longer looked that way after uprisings erupted in Sudan, Algeria, Lebanon and Iraq at the end of the decade. On the other side, arguments about authoritarian resilience which looked ready for the trash heap in 2011 came back with a vengeance during the transitional setbacks and autocratic resurgence a few years later.

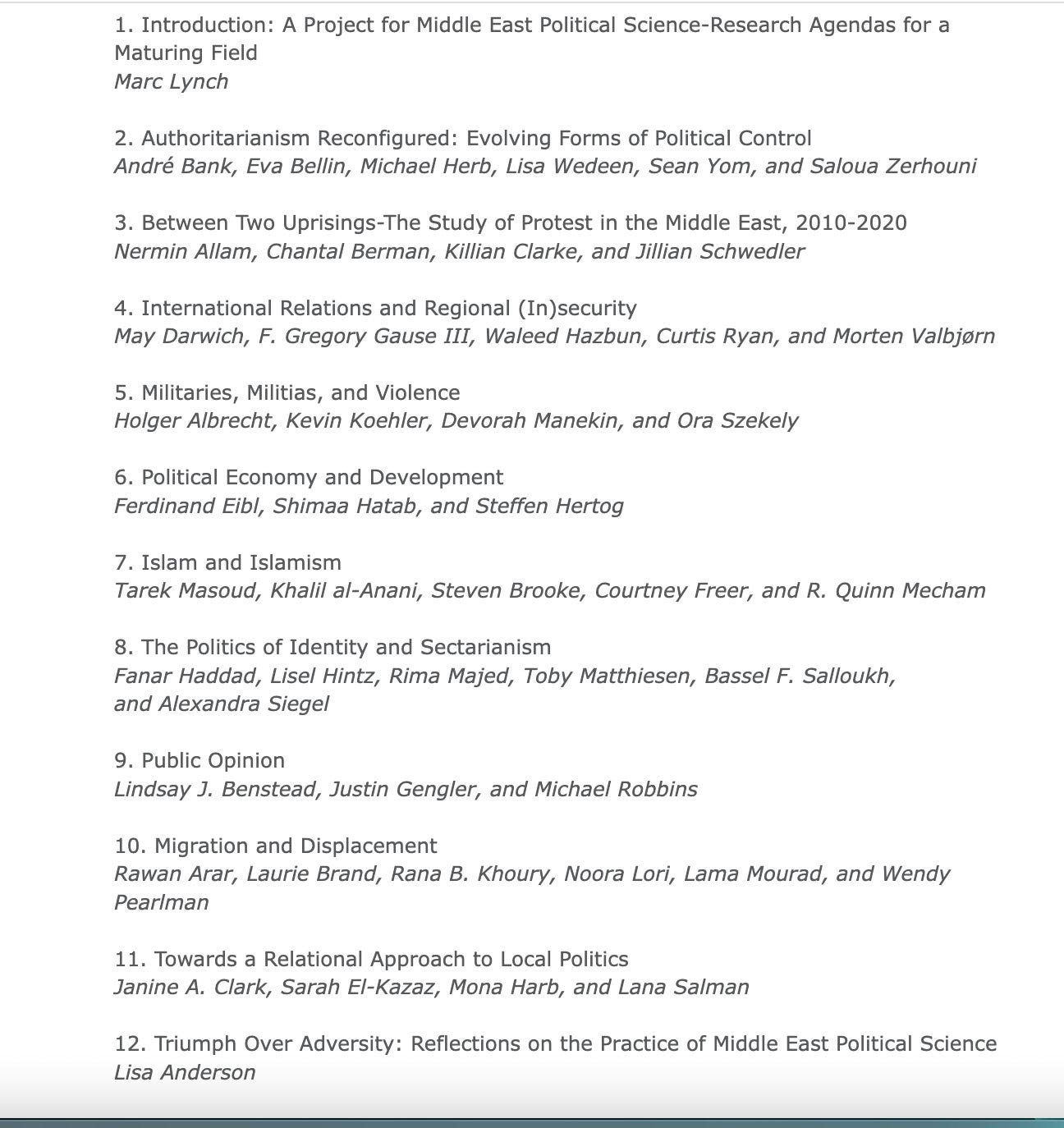

A few years ago, with various anniversaries of the Arab uprisings looming on the horizon, I used the annual conference of the Project on Middle East Political Science to organize a massive stock-taking enterprise. Out of that conference, ten working groups were formed, bringing together a diverse group of almost fifty scholars from all career stages, charged with writing a review essay style chapter assessing the strengths and weaknesses of Middle East political science research across ten different subfield areas: authoritarianism, protest and contentious politics, international relations, militaries and militias, Islamism, political economy, sectarianism and identity politics, survey research and public opinion, migration and displacement, and local and urban politics. A few working groups, such as one on women and gender, decided not to go forward in hopes that a gender perspective would inform all the chapters. After each working group had produced a draft chapter, we convened another online workshop where the full group discussed every chapter with an eye towards encouraging engagement across the chapters and highlighting points of agreement and disagreement. The great Lisa Anderson contributed a conclusion reflecting on the long trajectory of Middle East political science.

Jillian Schwedler, Sean Yom and I closely edited every chapter, ensuring stylistic consistency, pushing the authors based on our own perspectives and expertise, and constantly encouraging the groups to engage with the positions advanced in other chapters. We hope that you will agree that the resulting volume is far more than a collection of loosely related papers. It is a genuinely collaborative work representing a sustained dialogue about the state of the Middle East Political Science field across four dozen scholars coming from very different methodological, subfield, and analytical perspectives.

My introduction offers a different take on the state of the field than one usually sees. Here’s an excerpt:

“The Middle East field is in a crisis within the broader discipline of polit- ical science,” warned Jerrold Green in 1994. His long familiar complaint expressed a prevailing sentiment that would be repeated over the ensuing decades. Critics from within the academy… attacked the field’s insularity, resistance to methodological innovations in the broader discipline, preference for rich description over theoretical rigor, and failure to publish in top disciplinary journals. Some critics from outside the academy attacked the field for overpoliticization in opposition to Israel or American foreign policy, while others blasted it for its subservience to American foreign policy and security interests. The one point of consensus, across ideological and disciplinary lines, was that the field had failed.

In particular, Middle East political science was charged with a failure to anticipate the most important events and trends in the region. The field failed to predict the Iranian Revolution in 1979 and the rise of Islamism in the 1980s. It failed to predict Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990. It failed to anticipate al-Qaeda’s attack on the United States in 2001 (though it proved quite prescient in its warnings about the likely disaster of the 2003 invasion of Iraq). And, most recently, critics demanded to know “why Middle East studies missed the Arab Spring.” An influential postmortem in Perspectives on Politics, a leading disciplinary journal published by the American Political Science Association, argued that the field had failed to predict the Arab uprisings a decade ago due to its “focus on authoritarianism and the obstacles to democratization which marginalized questions relevant to the dynamics of popular mobilization, and deemphasized their potentially inherent importance aside from their relevance to regime change.”

In this context, the Arab uprisings of 2011 were an epochal, transformative event in the history of the region. They were also an inflection point for political science scholarship about the region. Middle East political scientists did far better in anticipating the 2011 uprisings than is commonly believed and excelled in producing real-time analysis as they unfolded. In its aftermath, our research field has shown dramatic and critical breakthroughs that defiantly clash with the depressing tone of past assessments. The uprisings generated an enormous demand for Middle East and North Africa (MENA) expertise, with both positive and negative implications; as with 9/11, instant experts and the immediate demands of U.S. policymakers could crowd out the work of serious scholars. But for those scholars, the uprisings introduced a dizzying array of productive new questions, new data, and new debates. Breaking with the decennial tradition of disciplinary self-flagellation, this book comes not to bury Middle East political science but to praise it. The decade since the Arab uprisings has witnessed an efflorescence of rigorous, deeply informed, and relevant research on the Middle East which rivals that of any field in political science.

This impressive performance did not come out of nowhere. Developments, both intellectual and sociological, within the field in the decade prior to the Arab uprisings had created a deep bench of scholars equipped with immersive area knowledge and strong methodological skills which were primed to rise to the challenge. More than at any time in the history of the field, this cohort of scholars was primed to produce rigorous academic analysis and to engage effectively with a hungry policy-oriented public. This deep bench was reinforced by the growing presence of scholars from the MENA region who were increasingly integrated into academic networks. After decades of marginalization, MENA scholars took a central position within key areas of political science, driving research agendas and being included organically in many of the broader debates across the discipline. Inasmuch as the Arab uprisings perturbed the landscape of the Middle East, the events also allowed Middle East scholars to begin transforming political science itself, particularly in areas such as research ethics and data transparency.

End excerpt.

The rest of my introduction, and the book as a whole, seeks to vindicate these bold claims about the field. I’d like to think that the Project on Middle East Political Science which I’ve been directing for over a decade has made some difference on the sociological side, at least, in building networks and supporting the scholarship of these exemplary cohorts. But the real energy and impact comes from the work of the scholars themselves - both in their own research, and in their remarkable willingness to support their junior colleagues through participation in research workshops (see my recent brief note in PS: Political Science and Politics for some details on how many people in the POMEPS network have volunteered their time to serve as discussants in our many article and book manuscript workshops. Hint: it’s a lot.)

For all that’s been achieved over the last decade, we’re collectively realistic about many continuing and emergent challenges to the field of Middle East political science. The increasing repressiveness of the region’s regimes and their hostility to social science research has made it difficult to do the kind of research which was momentarily possible after 2011: here I’ll just mention Guilio Regini, killed (almost certainly) by Egyptian security services while doing research in Egypt; Waleed Salem, who recently wrote about his detention and interrogation for doing research on the judiciary in Egypt; and Matthew Hedges, a British graduate student detained in the UAE for doing research on security policies. COVID disrupted research travel for several years. Disciplinary trends, from research transparency requirements to the fetishization of certain types of research, can disproportionately impact researchers working in areas like the Middle East.

We hope that The Political Science of the Middle East will be interesting and useful to everyone working in our subfield, of course, especially graduate students. Put it on your syllabi! We also hope that it appeals to non-MENA experts in comparative politics and international relations, who can see where our field has developed in relation to the broader literature. And we’ve written and edited it to be accessible to the non-academics who want to dip their toes into the scholarly research on the Middle East. We’re very proud of this book, and of the huge number of authors who contributed, and look forward to reader comments and reactions.

Get 30% off the paperback of The Political Science of the Middle East with code ASFLYQ6 or get the Kindle version currently on sale for only $9.99.