What Smuggling Tells Us About the State

Plus a new collection on religion and politics in Africa I edited and the usual wealth of scholarship in the weekly MENA Academy roundup.

Welcome back to MENA Academy Weekly Roundup #22, after last week’s much needed vacation! Those of us working on the Middle East — and not just us — continue to be overwhelmed at all levels by Israel’s ongoing war with Gaza. I’ve given several talks recently on Gaza itself and the regional repercussions of the war— one at the University of Washington’s Jackson School (video here) and another at Ohio State’s Mershon Center (video here); I’ll be writing up those talks into an article soon, I promise. On the knowledge production side, Shibley Telhami and I are giving a talk on Wednesday of this week at Cornell University about the fallout of the war for scholars of the Middle East, expanding on the results of our Middle East Scholars Barometer Survey and previewing some of the depressing (indeed shocking) findings of the MESA task force I’m chairing on the campus climate.

We start this week’s roundup with the book of the week, which I’m delighted to have published in my own series, Columbia Studies in Middle East Politics:

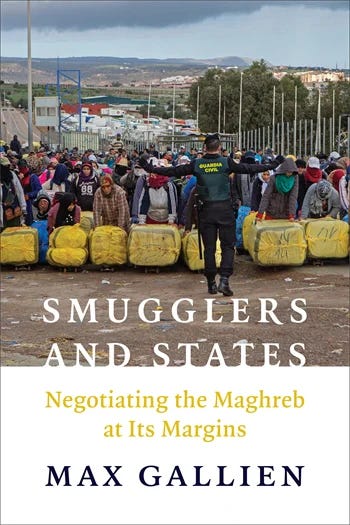

Max Gallien, Smugglers and States: Negotiating the Maghreb at Its Margins (Columbia University Press, 2024).

Control over borders is typically seen as one of the key attributes of stateness, with smuggling and illegal migration regularly targeted as dangerous indicators of state failure. In this innovative and closely observed political ethnography of borders in Tunisia and Morocco, Max Gallien demonstrates that these activities are often quite regulated and orderly — and under the right conditions reinforce stateness rather than undermine it. The flow of illicit goods plays a central role in local and national economies, which depend on their availability. Large scale flows of these unregulated goods can be a sign of a healthy state functioning as intended — and securitized efforts to harden borders in the name of preventing terrorism or drug smuggling can often have disastrous unintended impacts on not just smugglers but on the broader political economy.

Gallien’s focus in Smugglers and States is the ostensibly illegal trade in small consumer goods as well as gasoline and other economic essentials. His ethnography, focused on what actually happens at border crossings, reveals regularized and routinized passage of vast quantities of these goods under the watchful but noninterfering eye of state authorities. The book is rich with observations of the informal organization of these smuggling networks, enforced from within and governed by shared norms and practices which provide order from within apparent anarchy. He traces those networks from the border to the informal markets where goods are sold, showing their centrality to ordinary urban life far from sensationalized images of drugs and guns.

Smugglers and States is one of the most original and creative books I’ve read recently, and one I was really thrilled to publish in my Columbia University Press series. Gallien has really thoughtful things to say about the ethics and practicalities of doing this kind of research, and is able to place his hyper-local ethnographies into a broader global conversation about borders and formality. I read it as a political anthropology of the state with a challenging reconceptualization of state capacity, where what looks like weakness can be strength, and what looks like strengthening can have perverse implications. That could just be because state capacity is on my mind because of my and Steven Heydemann’s forthcoming book, but I expect readers will find a lot of fascinating threads to pursue in Gallien’s approach to the state literature as well as to the literature on networks, economies, informality, and transnational flows. This should be a must-read for MENA political science and well beyond the MENA subfield.

Gallien summarized a lot of the key ideas of the book in this recent essay for Tunisia’s Nawaat, if you want to get a taste for his analysis before picking up the book. joined the Middle East Political Science Podcast to talk about Smugglers and States last week. Listen to our conversation here!

Next up: Religion and Politics in Africa, a brand new volume of African Social Research which I edited based on a Program on African Social Research junior scholars workshop held in Dakar, Senegal over the summer. I wrote the introduction, along with my fantastic colleagues Bamba Ndiyae and Amy Niang. The dozen papers range widely across the continent and over history, taking on transformations and the political evolution of both Sunni and Shia Islam, Christianity, and traditional African religions. As a long time scholar of Middle Eastern Islamist movements, I found myself really fascinated by the similarities and the differences between the Middle East and Africa in both the literature and in the political realities - with the Maghreb occupying, as always, a critical position at the nexus (Tunisia’s Ennahda and Morocco’s Islamist movements look comfortably at home in the universe of Middle Eastern Islamism, but there’s a lot of other types of religious action going on as well). The analysis of religion and politics here is very much grounded in Africa, though, not an implicit or explicit comparison to the Middle East. Almost all of the authors are junior scholars working on the African continent, part of Pasiri’s growing transnational and continental network of African scholars; it was such a pleasure working with them. You can download the full open access volume free here; individual articles should be available for linking soon.

Next, for those interested in public opinion, the Arab Barometer has released its 2023 study of Tunisian public opinion. The gold standard for MENA survey research, the Arab Barometer has previously released some of the most intriguing results of the 2023 wave. But there’s a lot more here of interest to scholars of Tunisia and the Middle East more broadly (all the data is publicly available for download). It finds that economic optimism has dropped 14% since the last survey in 2021, shortly after Kais Saeid’s coup. Hunger has increased dramatically (two-thirds say that they went without food at least once in the previous month). Trust in political institutions, whether Parliament or the government, is very low; three-quarters say they have trust in Saied still, but only half rate his government’s performance favorably. Check out all the results here.

Finally, here’s two academic journal articles which caught my eye :

Ruth Hanau Santini and Paolo Wulzer, “The Evolution of the Gulf: History and Theories of a Complex Subregion,” Middle East Policy (March 2024). ABSTRACT: This article explores the relationship between international-relations theories and Cold War and post-Cold War historical dynamics in the Middle East, in particular the Gulf. It first identifies the theoretical approaches that have been applied or that have failed to be applied to the region's changing geopolitics, then delves into Cold War history and its impact on the Middle East and the Gulf by examining the crucial changes to the Gulf security system sparked by developments in the 1970s and the Iran-Iraq War of 1980–1988. The article next investigates the extent to which the interplay of post-Cold War regional conflicts and key events, from the Iraq wars of 1991 and 2003 to the Arab Spring, have impacted the Gulf subregional system. The final part scrutinizes the shifting intra- and extraregional Gulf politics and how theoretically informed approaches inspired by international political economy can accommodate these geopolitical changes. The article is part of a special issue examining the responses of Gulf countries to rising Sino-American competition, edited by Andrea Ghiselli, Anoushiravan Ehteshami, and Enrico Fardella.

Austin Knuppe and Matthew Nanes, “When Bullets and Ballots Collide: How the Dissolution of the Anti-Islamic State Coalition Stalled Iraq’s Transition to Peacetime.” Civil Wars (March 2024). ABSTRACT: Iraq’s 2017 victory over the Islamic State (IS) ushered in a period of political gridlock and electoral violence. Rather than demilitarising to compete in elections, pro-government militias retained their weapons while simultaneously providing public goods and services. Iraq’s experience presents a challenge to existing theories of civil war transitions, which suggest that wartime coalitions either fragment or demilitarise as peacetime approaches. Iraq’s stalled transition presents a third possible outcome—a stalled transition—which emerges from constraints confronting pro-government coalitions. Iraq’s ecosystem of ‘militia-party hybrids’ resembles Lebanon, Libya, Syria, and Yemen, where armed groups enter peacetime politics without fully demilitarising.