A History of False Hope

Lori Allen looks back at a century of Investigative Committees in Palestine

Lori Allen, A History of False Hope: Investigatory Commissions in Palestine. Stanford University Press, 2021.

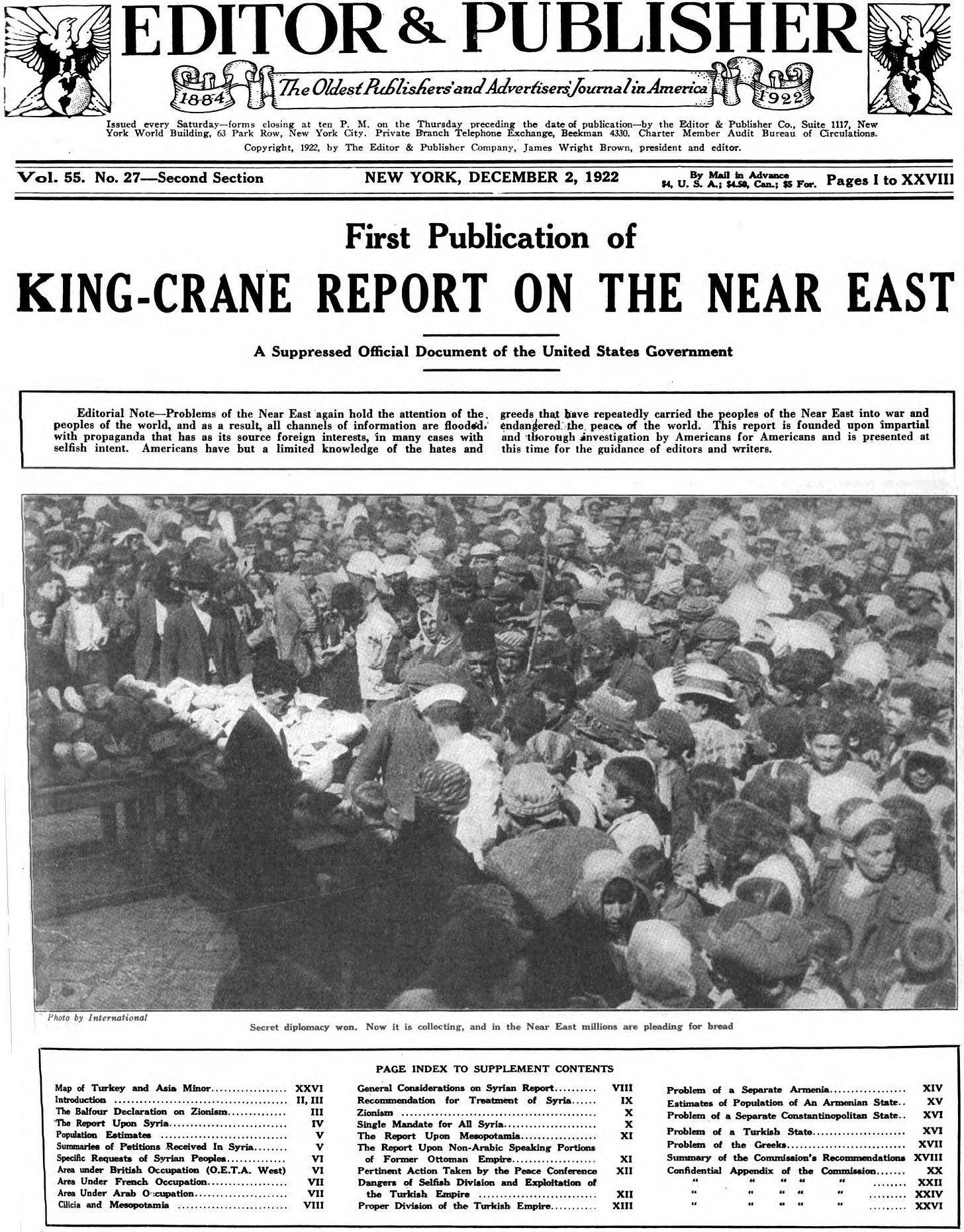

Image: King-Crane Commission, via Wikipedia

Palestinians have long looked to international law and international organizations to support their aspirations for their own state. This made good sense, in that the letter (and spirit) international law generally supported their claims to self-determination and, later, to the end of Israeli occupation. But, as Noura Erekat brilliantly showed in her recent book Justice for Some: Law and the Question of Palestine, there have always been sharp limits on the ability of international law to make a difference when it came to Palestine (or, really, anywhere). While international public opinion, international law and norms all certainly mattered in shaping the conditions and possibilities of political change, hard realities of material power and Israel’s unique positionality mattered more. The International Criminal Court wasn’t going to save Palestine any more than the United Nations or the International Court of Justice.

In A History of False Hope, anthropologist Lori Allen focuses her historical and anthropological lens on one aspect of the consistent failure of international institutional responses: the long series of investigatory commissions sent by various external actors to explore conditions in Palestine. Tracing the history of those commissions from the King-Crane Commission following World War I up to through the Goldstone Commission tasked with assessing possible war crimes in the 2009 Gaza war is instructive, indeed. Allen shows that Palestinians took these commissions very seriously, that many of these commissions worked sincerely to fulfil their charge, and that the commissions repeatedly failed to make any real difference. It is difficult to not conclude that “the maintenance of Palestinian unfreedom”, in Allen’s formulation, was the purpose and not an unintended failure.

Therein lies her twin puzzles. First, why did international organizations and states keep sending these commissions if they never followed their advice. She does not find the obvious answer, that they were a way to be seen as doing something during a crisis without actually doing anything, sufficient. Members of the commissions did seem to take their mandate seriously. She argues that the successive commissions worked to keep Palestinians engaged with international law and to internalize liberal sensibilities about how to best do so. Her second puzzle is why Palestinians continue engaging with them when they never ultimately helped. Here too, the obvious - they had few other options - does not satisfy. In each case, she showed, Palestinians argued among themselves about the value of engagement, and entered into the investigations purposefully with few illusions about their interlocutors.

A History of False Hope is a compelling work of ethnographic historiography, one which tries to view these events and processes through the eyes of the Palestinians living through them rather than only from the vantage point of colonial and international officials. One of the great strengths of Allen’s book is to show through the accumulation of detail how seriously Palestinians took these commissions and what they actually did in response. I found her invocation of the instantiation of new Palestinian and broader Arab public spheres especially compelling, especially in the early chapters. She shows really effectively how the debates over the investigatory comissions triggered both mediated and unmediated debates across broad publics, with a high degree of awareness of their mission and purpose.

Her account of the King-Crane Commission is exemplary. Drawing on a wide range of contemporary Arabic newspapers as well as the Commission’s own documents and other sources, she shows convincingly how a Palestinian public sphere emerged around the question of self-determination. The mobilization of Palestinian communities around open letters and testimonies to the Commission took place within the broader context of regional activism around demands for independence. Most histories of the period mention the strong support for independence expressed by virtually all Arabs who testified to the Commission. But Allen goes deeper, detailing the arguments within those communities, the discussions over strategy and rhetorical framing, the contests over representation, and the resonance of all of this at the popular level as well as among elites.

While it isn’t a primary theme of the book, she also shows the profound ignorance and Orientalism of some of the Commission members - her dissection of the racist, muddled and Orientalist assumptions in the 150 books ordered by the Commission shows how academics having policy impact might not always be a good thing! The disconnect between the unequivocal feedback to the Commission during its tour of the Levant and the imperial polices which followed established a familiar pattern.

The book’s chapters range over 100 years of Commissions which followed the King-Crane Commission. She devotes a chapter to the Peel Commission, one of the many investigatory committees sent by the British during their tumultuous mandatory rule. Palestinians engaged in an active insurgent uprising against the Mandate initially opted to boycott the Commission. They saw it, not incorrectly, as a bog standard British move to deflate the uprising and calm things down with the illusion of doing something. Allen also places their boycott within a rising transnational anticolonialism challenging imperial liberal internationalism. She shows how much attention the Palestinian press devoted to contemporaneous uprisings in Syria, Egypt and Morocco, as well as to Gandhi’s campaign against the British in India. They viewed the response of world public opinion and expressions of solidarity from other anticolonial movements to be consequential, a source of their strength and a key target of their rhetoric. Ultimately, the intervention of Arab rulers (many of whom were beholden, of course, to the British) persuaded the Palestinians to break their boycott and give testimony to the Commission.

Another chapter takes up the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry after World War II. Allen shows how global sympathy with the Jewish experience of the Holocaust shifted the terms of discourse, neutralizing some avenues of Palestinian argument and overriding ostensibly universal liberal-legal principles. Again, she shows how the Palestinians engaging with the Commission attempted to craft humanitarian arguments and appeals to democratic values. Another chapter details the operations of the UN Special Committee to Investigage Israeli Practices Affecting the Human Rights of the Population of the Occupied Territories (UNSCIIP), and the opportunities for solidarity at the UN General Assembly opened by Third Worldism.

The book culminates with paired chapters on more recent Commissions: the Mitchell Committee sent to find a way forward during the second Intifada and the Goldstone Committee formed to investigate alleged war crimes by Israel and Hamas during their 2009 war. Where earlier chapters required primarily documentary research, these mroe recent chapters offered the opportunity for Allen to interview committee members and their Palestinian interlocutors as well as to introduce some of her own enthnographic work in the West Bank during the events in question. Her research sheds light on the inner workings of those committees, what Palestinians hoped to accomplish, and the limits of their actual impact. She notes the importance of the shift towards a discourse of accountability for war crimes and human rights violations, a different way of engaging with international law than the earlier eras focused on self-determination and national rights.

A History of False Hope offers intriguing insights into a century’s worth of Palestinian engagement with international law and institutions. Ultimately, Allen is no more optimistic about the prospects for legal approaches than Erekat. But she makes a significant contribution by recovering the motivations, arguments, and social context for Palestinian engagement with those international commissions despite their shortcomings. I enjoyed this well-written book, especially the early chapters with their very effective use of Palestinian newspapers and other documentary sources. It would be useful to pair it with a comparable excavation of early Zionist and later Israeli engagements with the same Commissions over the years. But no one book can do everything, and this one succeeds on its own terms; recommended for anyone interested in the development of international law or the Palestinian experience.

Previous Abu Aardvark book review essays:

Sudan’s Revolutionary Struggle: Willow Berridge, Justin Lynch, Raga Makawi and Alex de Waal’s Sudan’s Unfinished Democracy.

Imperial Mecca: Michael Christopher Low’s Imperial Mecca

Sexting Like a State: Maya Mikdashi’s Sextarianism; John Nagle and Tamirace Fakhoury’s, Resisting Sectarianism

A New Political Economy of Islamism: Khalid Medani’s Black Markets and Militants

Man, the State, and Bread: Jose Ciro Martinez’s States of Subsistence

Where, and Why, is North Africa? Majid Hannoum’s The Invention of the Maghreb and Megan Brown’s The Seventh Member State

Why Does MENA Transitional Justice Fail? Mariam Salehi’s Transitional Justice in Progress

Why did Egyptians Cheer a Massacre? Mona el-Ghobashy’s Bread and Freedom and Justin Grimm’s Contested Legitimacies.

Jordan, Forever on the Brink… of What? Jillian Schwedler’s Protesting Jordan