Worldmaking after the Ottomans

A masterful new book uses a wide-angle lens to reframe what really happened during the creation of the modern Middle East

Jonathan Wyrtzen, Worldmaking in the Long Great War: How Local and Colonial Struggles Shaped the Modern Middle East (Columbia University Press)

My friend Daniel Neep published a provocative article last year under the Monty Python-esque title “What Have the Ottomans Ever Done For Us?” which challenged political scientists to discard their outdated notions about what happened towards the end of the Ottoman Empire (we talked about it on the podcast here). Neep alerted many of us, or at least me, to a rich new literature about that era which challenged prevailing assumptions and reframed what we thought we knew. With some helpful reading suggestions from Ottoman historian Howard Eissenstat, I decided to take up the challenge. Hasan Kayali’s Imperial Resilience: The Great War’s End, Ottoman Longevity, and Incidental Nations and Michael Provence’s, The Last Ottoman Generation and the Making of the Modern Middle East (listen to my podcast conversation with Provence here) were among my favorites in that post-Ottoman reading binge. As promised, they really did teach me something new about the institutional, political, military, ideational, and cultural milieu of an astonishingly turbulent era.

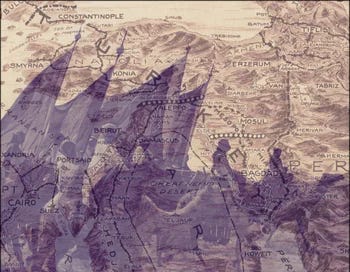

Jonathan Wyrtzen’s masterful Worldmaking in the Long Great War, just published last month by Columbia University Press (though sadly not in my series), is the most sweeping and panoramic of these new books. He makes a compelling case that the Ottoman Empire’s end needs to be studied within the extended period from 1911-1934, rather than the conventional reference to the 1914-1918 world war. He makes an equally compelling case for focusing on the big picture, highlighting the interconnections between developments across the Empire which are often treated in isolation. Like the other books discussed here, he shows very convincingly that the map which emerged from the wreckage of World War I were shaped as much by local contestation and continuing warfare as by the treaties negotiated by European powers. While Wyrtzen warns us in the conclusion about overly romanticizing what might have been, it’s hard not to reflect on the yawning gap between the endlessly open possibilities in those post-WWI years and the stifling reality of the Middle East which actually emerged from its ugly imperial encounter.

Debunking the importance of Sykes-Picot has long been an academic parlor game (not least during the brief period in 2014 when the Islamic State claimed to have overturned it). But Wyrtzen, in line with other recent scholarship, shows that none of the major post-war accords actually aligned with reality - not Sykes-Picot, not San Remo, not Sevres. The borders and polities negotiated by the colonial powers almost always faced local resistance which changed their ultimate forms; the final demarcation of the post-Ottoman map only really took hold in the early 1930s, and few of the mandate states were ever truly pacified by their colonial overlords even after the deployment of extreme violence. It took far longer than is generally remembered for the fluid postwar world to crystallize into our familiar map - and that map’s details were far from inevitable. Wyrtzen reminds us of the disappearance of new polities such as the Rif Republic or the Kingdom of the Hejaz, the survival of which would have appeared obvious in retrospect given its cultural power and the Hashemite alliance with the British but which in this reality fell to the onslaught of Saudi statebuilding.

Wyrtzen emphasizes “worldmaking” in its multiple meanings: not just the making of the maps, but also the identities and ideas which emerged through the process of political engagement and military combat. War, he writes, “unmakes political orders and… provides the conditions in which new political worlds can be made.” (I detect an echo here of the classic volume edited by Steven Heydemann twenty years ago on war and state-making in the Middle East). The postwar period saw the rise of new elites attentive to the suddenly open vista of potential political arrangements, each of which “rapidly transitioned between becoming thinkable and unthinkable”. Wyrtzen’s account of their worldmaking on the fly resonates especially nicely with Provence’s detailed descriptions of the lives of post-Ottoman military officers and other elites navigating the new political landscapes (often ending up as high ranking officials in the new ‘Arab’ states).

Violence, not juridical or diplomatic decisions, lay at the heart of these challenges. Local actors always resisted colonial plans and imposed facts on the ground which bore little relationship to those outlined in treaties. Their resistance was sometimes successful, as with the military campaign led by Mustafa Kemal to establish the new Turkish Republic in the Anatolian core which swept aside the terms of the treaty of Sevres and forced recogntion under the treaty of Lausanne. Most of these Middle Eastern counter-polities were defeated, but that should not distract from how fierce they were and the enormous costs they imposed upon the colonial powers. Wyrtzen tracks large scale violent challenges in Syria, Iraq, Palestine, Morocco, Libya, the Kurdish ares in Turkey, and more - each put down only with massive deployment of force by the mandatory or colonial regimes. Each seriously challenged the postwar settlement, even if each ultimately failed. As Wyrtzen sums up, “none of the modern polities or borders in the greater Middle East were unilaterally imposed; all were negotiated over time; and virtually all were actually defined and demarcated not with the stroke of a pen but after extended periods of warfare.”

Wyrtzen’s “wide-angle lens” helps to show the interconnections between a wide range of seemingly disconnected events which are usually studied in isolation from one another (something I tried to do, for better or worse, in my book about the post-2011 Middle East, The New Arab Wars). People closely watched and learned from events happening elsewhere in the broader imperial and regional context: the Rif Rebellion showed would-be rebels in Syria that colonial powers could be defeated, Palestinians studied uprisings in Syria and Iraq. Expensive counterinsurgencies in one country strained the resources available to the colonial power in others, creating political and military opportunities. This all works extremely effectively. Beyond just the interconnections, Wyrtzen calls out the tradition of studying these processes through the retroactive lens of particular countries - Morocco, Turkey, Syria, Palestine, etc - which did not exist at the time and did not necessarily have to exist. The wide angle lens helps us to avoid the fallacy of assuming that what happened had to be, or of believing that the actors at the time operated from within that particular national lens.

These exercises in worldmaking began before 1914 and continued long beyond the formal end of the war in 1918. On the front end, Wyrtzen shows how Ottoman reform efforts in the face of cascading political defeats opened vistas for challengers from within all corners of what remained of the empire, while a crisis emanating from European colonial competition in Morocco in 1911 shaped the conditions for the 1914 crisis which sparked the eruption of full scale war. As a side note, Italy emerged as more important in this narrative than I had perhaps expected - not just in the brutality of its systematic devastation of Libya’s population (see Ali Ahmida’s recent book making a strong case for calling it genocide) - but also in the scope of its aspirations on the Arabian peninsula and in core Ottoman territories including a 1912 push against Istanbul itself.

On the back end, he demonstrates that the battles over the shape of the postwar region continued militarily, politically, and ideationally until at least the early 1930s. He excels at demonstrating the interconnections, such as the ways competition over Ottoman North Africa metastasized into the Balkan campaigns or “the nearly synchronic Kurdish, Riffi and Syrian jihads” of 1925. He dates its end to the completion of the French conquest of Morocco, the Italian unification of the constituent parts of Libya, and the Saudi-Yemeni peace treaty, though the 1936 Palestinian revolt seems to fit quite naturally into the narrative. More broadly, he shows the broad imperial context of that war, including not only its global reach but also the ways in which imperial interests - and resources such as manpower and raw materials - shaped the European war. In his words, “de-Europeanizing the Great War by Ottomanizing it underscores how the greater Middle East was central to the causes, course of, and outcomes of World War I as a whole.”

Wyrtzen also shows how the emergent map concealed wide variations in the actual scope of state, imperial or colonial control, with a particular eye on the emergence of non-state governance by challengers such as the Rif Republic, the Sanusi polity fighting against Italian occupation of what would become Libya, Kurdish opponents of their division by the emergent state order, Palestinians and the evolving Zionist Yishuv each contesting the British mandatory regime, and the Saudi statemaking expansion across the Arabian peninsula. Those movements were not simply imagining political alternatives, they were making them into realities on the ground in defiance of European imperial dictates. That many of them were defeated, again, should not take away from the significance of the attempts or from the legacies and memories which they generated through their efforts.

Immersion in this world which seemed so wide open and full of hope really can be difficult knowing what we know about the political trajectory of the MENA region. With each new revolt, I found myself rooting for the challengers to win this time, to force the colonial mandates out and realize some of those alternative possibilities. Wyrtzen reminds us towards the end that there are no guarantees that things would have turned out better had the map turned out differently. But, as with Lori Allen’s recent discussion of the King-Crane Commission (see my review here), I still came away from his account wistful for lost possibilities and frustrated by how close some of these challengers came to changing the trajectory of colonial history.

Overall, Wyrtzen’s Worldmaking in the Long Great War succeeds brilliantly on its own terms. While many of the individual episodes may be familiar (though some have been recovered from the dustbin of history, as they say), he puts them together in new ways to tell a compelling story of worldmaking under conditions of both local and global uncertainty. In many ways, this is the single book on the era that I had been looking for — and as such is highly recommended for courses looking for such an historical overiew.